Deep Ends

Fragments from Prospect.3

–

Prospect New Orleans’ biennial Prospect.3: Notes for Now (P.3) was a phenomenal undertaking curated by Franklin Sirmans that looked at the multifaceted history of New Orleans through cross-cultural perspectives. This photo essay is one of three archival encounters which left an indelible mark on me as a searcher, prompting introspection about New Orleans’ unique position in the global North/South polemic.

“No matter how deeply you come to know a place, you can keep coming back to know it more.”

I. Fragments within fragments

In this line of cultural work you have to manage your expectations, and oftentimes it is the hardest thing to achieve. But, once in a while, you become surprised when a moment manifests; within the same breath of cynicism, at the edges of an exhale, at the crux of true worth—an ideal is revealed. I met Brooke Davis Anderson, Executive Director of Prospect New Orleans—the large-scale international art biennale turn triennial [1]—in August 2013 as I was making my way back to the Caribbean. I got wind of Prospect.3 earlier in the year through social media, and kept it in the back of my mind for most of my summer. We sat together and she shared the mammoth task of producing Prospect.3.

Anderson spoke clearly and passionately about the project’s transformative potential, and in heartening ways about the revitalisation of New Orleans through its powerful art and culture. With an almost impossible goal of raising four million dollars and challenging the model of art biennales, Anderson and her modest core team of three have pulled off something extraordinary, self-aware and critical for our time.

Anderson uprooted from New York, family in tow, and has been working in New Orleans since October, where she will be stationed until its closing. Prospect’s main office, and the entire ecology of the emerging biennale, is now centred in the city. What that means is that Prospect New Orleans is considering its position as being a formative entity that operates in a local way, developing a sustainable future by introducing itself as a non-profit endeavour which actively works to contribute to the cultural economy of New Orleans and the Louisiana Gulf region.

In New Orleans, regular directional coordinates are ignored, and there is no such thing as North. Instead, the flow of things is demarcated by riverside, lakeside, uptown and downtown; the Mississippi River and Lake Pontchartrain turn this meandering landscape into a crescent. From the marshlands of the bayou, its subterranean life support, centre for trade and its new growth, gentrification showed its structure and reveals the underbelly of the societal underpinnings of a complex and soggy America. Concepts like syncretism, antropofagia, hybridity, primal instinct and intuition are organically proliferated out of spaces like New Orleans—spaces that make no sense, spaces of deep paradox, dirty histories, traumatic and vibrant presents. I was in a place where the South meets South, but also where there was no South, and it in turn goes on to become aqueous; an unending grave of water. It is by no mistake, but by a reinforcing geography, that New Orleans finds its surface six feet below sea level; is this city then a mystic graveyard?

Intrinsically I understood that the time promised to me here would be special. That its comparison to being the northernmost part of the Caribbean[2] would resonate, and the blossoms seen on my arrival were in fact familiar—so familiar that I didn’t know the name, just the shape, the colour and its variations. These blooms marked the beginning of a series of dots that drifted and connected, not unlike the atlas of this place.

Familiar night blooms. Image courtesy of ARC Magazine.

II. Three times a charm

Crescent City, the location for the rejuvenated Biennale Prospect New Orleans, was birthed by Dan Cameron in 2008 as a way to revitalise the city in the wake of the devastation caused by Hurricane Katrina. This third iteration opened on October 25, and runs through January 25, 2015. It hopes to attract upwards of 50,000 viewers and contribute to the ongoing renovation and reestablishment of a creative economy through cultural efforts, providing sustainable and viable models for future incarnations. Prospect.3’s ambitions are behemoth, but not impossible.

Prospect.3: Notes for Now supports the work of 58 artists, and at its creative helm welcomes the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) Curator and Department Head of Contemporary Art Franklin Sirmans as Artist Director. Sirmans’ effort is conversational, contemporary, poetic and politically charged; at its best, the collection of work sets up a new understanding of the social purpose of a biennale working in context with its location. To say the work is diverse or has a multicultural slant is an understatement; it is the central element, and the amassed collection highlights the work of artists of colour. African Americans, Caribbean artists and artists from the African diaspora constitute its centre. Along the periphery of this kind of support, Sirmans takes on the challenging job of reorienting and challenging the canon of art history, and the way in which its legacy has been passed on and is currently being practiced in the West. Of the 58 artists supported, 44 are artists of colour, and they pull no punches.

Drawing inspiration from Walker Percy’s novel ‘The Moviegoer’, Sirmans used the text as a structural entry point, grounding concerns that reflected upon themes like The South, Crime and Punishment, The Carnivalesque, Seeing Oneself in the Other, and The New Orleans Experience. During the press launch at the Ashé Cultural Arts Center, Sirmans opened with a vulnerable and thoughtful message highlighting the fact that he looked at the work and programming comprising Prospect.3 as a way to extend and open up a cross cultural discourse between international and local artists. Central to this discussion is the intersection of literature and art, and the quest for something that cannot be determined or essentialised, but constitutes a discrete series of conversations and fragments that engage with global aesthetics, ideas and currents.

Portrait of Terry Adkins. Photo by LaMont Hamilton Photography.

Sirmans dedicated the opening of P.3 to the late Terry Adkins, who passed away in early 2014. Adkins challenged Sirmans, asking him ‘what are you doing for us?’ I have come to view the work with this question on repeat in my mind, beginning to understand the purpose of Sirmans’ curatorial framework and the absurdity and impossibility of answering this question within an action. The responsibility and legacy of supporting people of colour in a way that coheres education and entertainment is no easy undertaking; the politics of representation, working through traumatic pasts while keeping an invitation to dialogue is the mystery and quiet agency of Prospect.3.

It arrives in the here and now, gives you room to invest in and question histories, multiplicities and sometimes, in the places that it shines, makes room for interrogation, re-negotiations, counter narratives and rebuttals.

III. The City that Care Forgot

So, the Superdome is right outside of my window.

No lie.

It seems farcical and a bit heretical.

Superdome. Image courtesy of ARC Magazine.

Not ever having visited NOLA (New Orleans), through the media saturation in 2005 the dome became a contested marker of modern American politics. The view bothered me, so I ended up pulling the drapes and only allowing light to seep through on an angle that made the dome invisible. Not so long ago, it was a refuge for thousands of people, the victims of Hurricane Katrina. In the aftermath of the disaster, the dome shone a light on the discrepancies and the insidiousness of American politics, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and the established powerful oligarchy: the 1%. This moment reaffirmed the nature of discrimination and the underlying racism that continues to proliferate across the American South in the devaluing, marginalising and dehumanising of a group of people.

Alec Soth’s seminal photo documentary project ‘Sleeping by the Mississippi’, two images that my father took during his work as a marine engineer in the 60s and 70s on a ship called ‘Panky’, along with Rebecca Solnit and Rebecca Snedeker’s ‘Unfathomable City: A New Orleans Atlas’, and ‘Our Great Disaster’ are my references for this place.

Fittingly, the press junket started off with a visit to the George and Leah McKenna Museum of African American Art which showcased multimedia installations by Carrie Mae Weems, preeminent artist, educator and mentor. Two distinct bodies of work are supported, including photographs from the Missing Link series and the video ‘Meaning and Landscape’, which retells and frames a historical thread born of sexual independence and questions the normative representations of historical dominance and submission, especially male/female plantation narratives. The silhouetted dance subverts roles that govern contemporary discourses and reevaluate historicised stories connected to memory and gendered roles. Alongside these, twelve images from Weems’ larger multimedia work ‘The Louisiana Project’ (2003) depicting the bicentennial of the Louisiana Purchase are presented in a minimal arrangement. The artist places herself in various locations: plantations, cemeteries, railroad tracks and the like, her body confronting and challenging these fraught and weighted backgrounds. Weems uses her body as a surrogate for the African American experience and tackles tenuous aspects of belonging, history and cultural identity.

On the second floor, the installation ‘Lincoln, Lonnie, and Me – A Story in 5 Parts’ (2012), offers an alluring welcome into a bygone era. Weems constructs an area where viewers are barricaded and greeted by darkness, a constructed stage, blood red hues and a chimera hologram borrowing from the 19th century ‘Pepper’s Ghost’ illusion/construction. ‘Lincoln, Lonnie, and Me – A Story in 5 Parts’ examines several scenarios that continue the ongoing tension of representations surrounding the black body.

Carrie Mae Weems. Lincoln, Lonnie and Me - A Story in 5 Parts. 2012. Installation shot from The George and Leah McKenna Museum of African American Art.

Haunting voices whisper tensely over an undercurrent of blues and Blind Willie Johnson’s ‘Dark Was The Night, Cold Was The Ground’, we hear the artist in her low, earthy voice beckon: “I have seen you. And I know you. I know you don’t believe me, do you? But I’m gonna take ya and I’m gonna break ya. Cuz I want you to know the suffering I know. It’s not gonna be pretty…” In an equivalent tenor, Weems ends slowly with “Revenge is a motherfucker.” The seduction here is enthralling as Weems’ voice welcomes with the tension of a trickster, temptress and rebel. Apparitions float and morph into bodies that are studied and probed, bodies that are on display moving between minstrelsy, mimicry and overt sexuality. In one scenario we see a woman lying on the floor, the curtain framing her lithe form, while a floating cloud of smoke and ashen rain cover and obliterate her physical being. She looks longingly into a mirror, searching for her identity, then silence beckons and relinquishes and the soft spell of jazz takes over. The narratives continue to build until it crescendos into a visual loop of President Kennedy’s hand as it is raised mid-wave during the motorcade on the day of his assassination. This gesture is played over and over until the iconic scene is imprinted and fixed in this motion of stasis; within a continuum that collapses poetics, history and power.

The Contemporary Arts Center of New Orleans, set in the historic downtown, houses the majority of works for Prospect.3: Notes for Now. Its collection showcases contemporary approaches to universal issues and heavily supports photographic and video works. Peruvian born, Berlin based artist David Zink Yi, working primarily in video, photography and sculpture, debuts his two-panel video installation ‘Horror Vacui’, the two-hour opus showcasing a rehearsal of a Latin band and interspersing footage showing rituals that are rooted in Afro-Cuban culture. The visual syncopation and syncretic assemblage breaks down culture complexity into beats, fragments of the body and its motion, and equivalent shots that reflect a community that has opened itself to the artist. There are shots of old men on porches and older women dancing to a rhythm that is enticing and intensely religious. Some of the imagery is abject, some tantric. All of it grinds into a rhythm that slowly engorges the space and moves from moments of silence and nothingness into an enormous filling.

David Zink Yi. Horror Vacui. Two-channel video installation. 2008. Displayed at the CAC, New Orleans. Image courtesy of ARC Magazine.

These moments are often private, held in discrete locations and communities, but Zink Yi’s attachment and obvious work over the years that he lived in Cuba allowed entré and provided us with a chance to consider cultural identity and the complicated relations of a Caribbean space. Here we can assess Yoruba, Santeria and the plethora of cultural deliveries and markers that make moments like these possible within an Afro-Caribbean setting—and there is an irony that makes this piece indeed afraid of emptiness.

New York born, New Orleans/Paris based photographer and curator Sophie T. Lvoff has lived in New Orleans since 2009. A selection of 10 photographs from the series Hell’s Bells/Sulphur/Honey are on view and follow a deep tradition and love for documentary photography. Looking at the work, it is easy to see that her palette, composition and refinement—in style and language—have been influenced by William Eggleston, Larry Sultan and Walker Evans. These are inviting surfaces, detailing a New Orleans that borders on the beautiful; however they refuse to enter into a dialogue of reduction.

Sophie T. Lvoff. St. Claude Avenue (Saturn Bar 1). Archival Pigment Print. 2014.

Images like ‘Steamboat Natchez (Calliope)’, ‘St. Bernard Avenue (Sardine)’, and ‘St. Claude Avenue (Saturn Bar I)’ capture the spirit and light of a liminal and profoundly psychological space; a place in between moments of beauty and collapse, bordering on a typology of destruction. Broken cars, overgrown fences and overly embellished interiors and exteriors depict a kind of natural and artificial decadence (excess) and richness that subsumes and demolishes the patina of everyday life. Lvoff’s formalism is to be complimented.

IV. The Edges of the South

Thomas Joshua Cooper’s images have intrigued me for a long while. I have followed his work closely over the last year in particular, due to the fact that I am collaborating with a photographer whose work deals with landscape and psychological space. I was surprised to encounter the material of Cooper’s ‘Drowned Trees – A Mississippi River Tree Line’, a series that the artist started in 2010 and completed this year. Cooper trekked the entire coastline of the Mississippi River and its Delta, investigating the phenomenology and the true spirit of the place. Half Cherokee[3], Cooper’s study deals with the topography of this meeting, but inherently Cooper is also tracking a spirit, renegotiating trails and boundaries closely connected to how the Americas were colonised. Nine modest prints were supported and, easily in their technical presence, coupled with the mythology of the River’s line, remarking on the essence of the south.

Thomas Joshua Cooper. Looking West towards Exile and the Trail of Tears / The Lower Mississippi River (East Bank). Selenium-toned chlorobromide gelatin silver print . 20 × 24 in. 2010/14. Courtesy the artist and Lannan Foundation, Santa Fe, NM.

“This search within a traumatic landscape helps to demystify signifiers that have come to define this space. The landscape broods between dark exhaustion and murkiness, presenting a cognitive reinterpretation of the ‘Trail of Tears’.”

Cooper’s patience echoes the search Sirmans alluded to in his formal essay for the P.3 catalogue. This search within a traumatic landscape helps to demystify signifiers that have come to define this space. The landscape broods between dark exhaustion and murkiness, presenting a cognitive reinterpretation of the ‘Trail of Tears’. The beauty and spectre of these images can quickly rescind into sentimentality, but Cooper’s inquisition as objective explorer adds leeway for viewers to contemplate the longing, loss and abundance of this swampy collection.

Cooper, a master at his art, uses the technical aspect of photography long gone, utilising the f.64 method with an old 1898 Agfa box camera to produce a Mississippi very different from the formalism in Soth’s ‘Sleeping by the Mississippi’. Cooper’s images probe American identity and land ownership, and bring to the surface hidden tales co-opted by hegemonic silencing. In America, it is often hard to access alternative and multiple images that deal with indigeneity. Even following this trail through the surface, it is difficult to see these details in Cooper’s work; the fog and mist are there to allow us to imagine these landscapes before the rupture of time and modernisation.

Thomas Joshua Cooper. Sunstruck and Blasted / Looking towards the Head of Passes / The Lower Mississippi River (West Bank). Selenium-toned chlorobromide gelatin silver print; 20 × 24 in. 2010/14. Courtesy the artist and Lannan Foundation, Santa Fe, NM.

V. Close Encounters

Newcomb Art Gallery at Tulane University hosted the exhibition ‘Totems Not Taboo’, showcasing the work of four artists: Andrea Fraser, Monir Farmanfarmaian, and two Caribbean heavyweights—London-based, Guyana-born artist Hew Locke and Jamaica-born, US-based artist Ebony G. Patterson. Locke and Patterson have had a growing level of interest in their practices and have been making eloquent and refined work for the international art market. I encountered their works at Untitled, Art Basel Miami Beach last December with their galleries Hales Gallery (UK) and Monique Meloche Gallery (Chicago).

Ebony G. Patterson …and then-beyond the bladez (detail). Mixed media on paper. 105.3 x 92.4 inches, (3 parts: 105 x 21 inches; 105.3 x 50.2 inches; 105 x 21.2 inches). 2014. Image courtesy of the artist and Monique Meloche Gallery, Chicago.

Patterson’s work has long revolved around a discourse of the gendered body and the politics of dancehall. In this most recent work, there is a serious departure from this subject matter, instead focusing on security, mortality and the grotesque. The five large-scale collages utilise the usual embellishment, but now have traces of loss that previously felt hidden beneath the baroque opulence of the surfaces. Are the surfaces still beautiful? Extremely, but the abundance and overwrought tension and didactic-ness feels less present, which allows for a more involved reading of these black male bodies that lay splayed with bleached faces and blinged-out accoutrements that offer relief.

Patterson’s surfaces are confrontational. In ‘…and then – Beyond the Bladez’, are we looking at a reworking of the yellow brick road? Here, there is no Dorothy, no Oz, but maybe there is a wizard, and in this make up the bricks are stained red. There is a colossal reworking of the environment where the paper holds paint, brooches, sequins, glitter, patterns of kitsch cloth, Victorian pins, ribbons, lace and silk—bejewelled enough to allow us to configure another mythology addressing the future of the Caribbean male. There is danger and loss in the eyes of the subjects, a kind of longing that reinforces demise. Here, death bares beauty, a kind of peace and retreat that continues the narrative device that Patterson has worked hard to master.

Ebony G. Patterson …and then-beyond the bladez (detail). Mixed media on paper. 105.3 x 92.4 inches (3 parts: 105 x 21 inches; 105.3 x 50.2 inches; 105 x 21.2 inches). 2014. Image courtesy of the artist and Monique Meloche Gallery, Chicago.

These tableaux reiterate the Caribbean’s historical and cultural connection to masquerade, the birth of a kind of history reinforced and made powerful by the lens of magical realism, surrealism and heightened aspects of performativity that are vital to the region. Beyond that, Patterson’s work is now in dialogue with several contemporary discourses, initiating healthy discussion by blending seduction and deception within these large-scale works.

Locke on the other hand had the opportunity to create the fourth incarnation of ‘The Nameless’. It is the second time the project has been supported in the United States, the first being in Atlanta in 2004. The piece, consisting of black plastic beads and thin black rope/chord, took two and a half weeks to install, and in its current incarnation acts a little like a cultural melangé. Locke borrows from histories, religion, fantasy, folklore, the Global South, literature and philosophy. He dredges up symbols and metaphors that contradict an easy reading rife with colonialism.

Hew Locke. Detail shot of The Nameless. Installation at Newcomb Art Gallery. 2014. Image courtesy of the artist and Hales Gallery.

At his artist talk he spoke about the construction and symbolism utilised, which borrow from a rich tradition of craft, yet are seen in the context of Notes for Now as having a ripe connection with the city of NOLA and Mardi Gras. Moving across St. Charles by streetcar, the neutral ground (partition in the middle of the road) is clear. Hanging from the electrical wires and gargantuan oak trees, beads are strewn in clumps across these permanent fixtures as a memory of a time where the second line, krewes and floats patrolled down this path.

“Ancestral icons float singularly across the walls, and if you are able to hone in on any one scene you will see that you are looking at Gypsies, the Tonton Macoute, Lord of a legion, winged lions, monkeys (lots of them), skulls, and goddesses with Kalashnikovs, the afterlife and death.”

The imagery in Locke’s ‘The Nameless’ attests to an assimilation and revelation of a kind of cultural hybridity, fusion and stream of consciousness that is significant and birthed out of the experience of colonialism and multicultural experiences. Ancestral icons float singularly across the walls, and if you are able to hone in on any one scene you will see that you are looking at Gypsies, the Tonton Macoute, Lord of a legion, winged lions, monkeys (lots of them), skulls, goddesses with Kalashnikovs, the afterlife and death. There is a lot of death present in the pomp and pageantry of Locke’s installation, and stars pinned all around as a device to keep characters in place. Standing before the installation as the people emptied out there is a votive sensation across the surface of this work. It is hallowed ground, the procession of figures across the wall seem like they are going to battle, but maybe they are here, still waiting for another moment when the artist plays Lord and arranges another procession, another powerful wielding.

Hew Locke. Mosquito Hall. 2013. Image courtesy of the artist and Hales Gallery.

Along with The Nameless, two large painted photographs are presented, ‘Mosquito Hall’ and ‘Tranquility Hall’, placed on walls opposing each other. These beautiful images present abandoned houses that are falling apart and returning to nature; they float in the rising water of the Essequibo with the ebbing levels of land erased—almost acting as ephemera. The tropical surroundings engulf their physicality as the flora erupts in greens, mustards and browns; hues that reference a return to nature. At the top of these ghost houses rise women; light-skinned female figures that carry children and newborns in their arms. These women are voluptuous and ooze sexuality, the creolised woman tempting you into surrender. Locke here uses the reference of the ‘One Drop’ to speak about the great rape, miscegenation, and the hybrid make-up of the nation of Guyana.

VI. The Mi-ssi-ssi-ppi

Besides being one of the first long words that you learn to spell growing up, the Mississippi, for those who haven’t seen it exists in Country and Western songs, the blues, Literature and in Cinema. From the iconic spread of New Orleans in ‘A Streetcar Named Desire’ (1951), with a brooding Brando and sultry Leigh, to Jarmusch’s tawdry and gritty ‘Down by Law’ (1986) and modern day epics like ‘Beasts of the Southern Wild’ (2012), the South is an iconic, murky establishment.

Bahamian-born, US-based artist Tavares Strachan’s work has been on the lips of the art world for the last three years. Pulling off the herculean feat of arriving at the 55th Venice Biennale in 2013 and presenting the first pavilion from the Anglophone Caribbean, Strachan unveils his most recent monumental project at P.3 titled ‘You belong here’. Close to a hundred people lined up and followed a tour led by Timothy “Speed” Levitch. Speed’s quirks and idiosyncrasies made the dying light of my first evening part fable. We were led from the Old U.S. Mint fence along the Esplanade, across Elysian Fields Avenue and French Market Station railway tracks into a docking and wharf area. Speed’s dramatic and overt personality set the perfect tone for the unveiling of Strachan’s neon work. As the roll-up gate was hoisted, we were greeted by the untamed waters of the Mississippi ahead, to the right the billowing lights of downtown New Orleans back dropped by a crimson sky, and to the left—housed on a 120-ft barge pulled by a modest tug—Strachan’s sculptural neon teased us as it was turned away from viewers on the wharf. Slowly, the entire 100-foot piece was revealed as the captain eased into a slick 180º.

Tavares Strachan. You belong here. Floating on the Mississippi River. 2014. Image courtesy of the artist.

The revelation of the words ‘You belong here’ engage with a kind of subliminal, personal and collective politics. Given the contentious history of New Orleans, the embedded dialogue makes light of class and racial concerns that have proliferated and continue to live within this space—social and psychological. Strachan has given us a monument to ponder, one that will incite conversation about belonging, ownership and visibility/invisibility.

Strachan and company, in conjunction with the unveiling, have also launched an app that will allow a wider public to comment on the work and learn more about the cultural and historical demographics of New Orleans. According to the press release on the project, “Every dollar raised from the sales of the app will be donated directly to Platforms Fund and Big Class, two New Orleans based nonprofit programs with a commitment to the grass roots development of New Orleans through culture and education.”

As the barge crisscrossed our peripheral vision, the voice of the piece became bolder; Strachan is bold. His objective is to confront, to displace and challenge works that have come in the canon before him. Like every great conceptual artist working with ideas that are about a social consciousness and awareness, he has developed a language that is tight, poetic and unafraid of unearthing our truths.

And so it happened like that: the revelation of the scope of Prospect.3 in 24 hours. These words are a variation, a multiple in the multitude of narratives that can describe this place and this project. ‘You belong here’ consists of the opposing qualities that also make it buoyant. That transitional space of being one thing yet being numerous things, and to a person, maybe something outside of that, maybe something inside—but it doesn’t matter. These variations provide us with the possibility of entering another realm with empathy, understanding and compassion. What will happen if we all belong?

What a radical idea, what an impossible but hoped for reality.

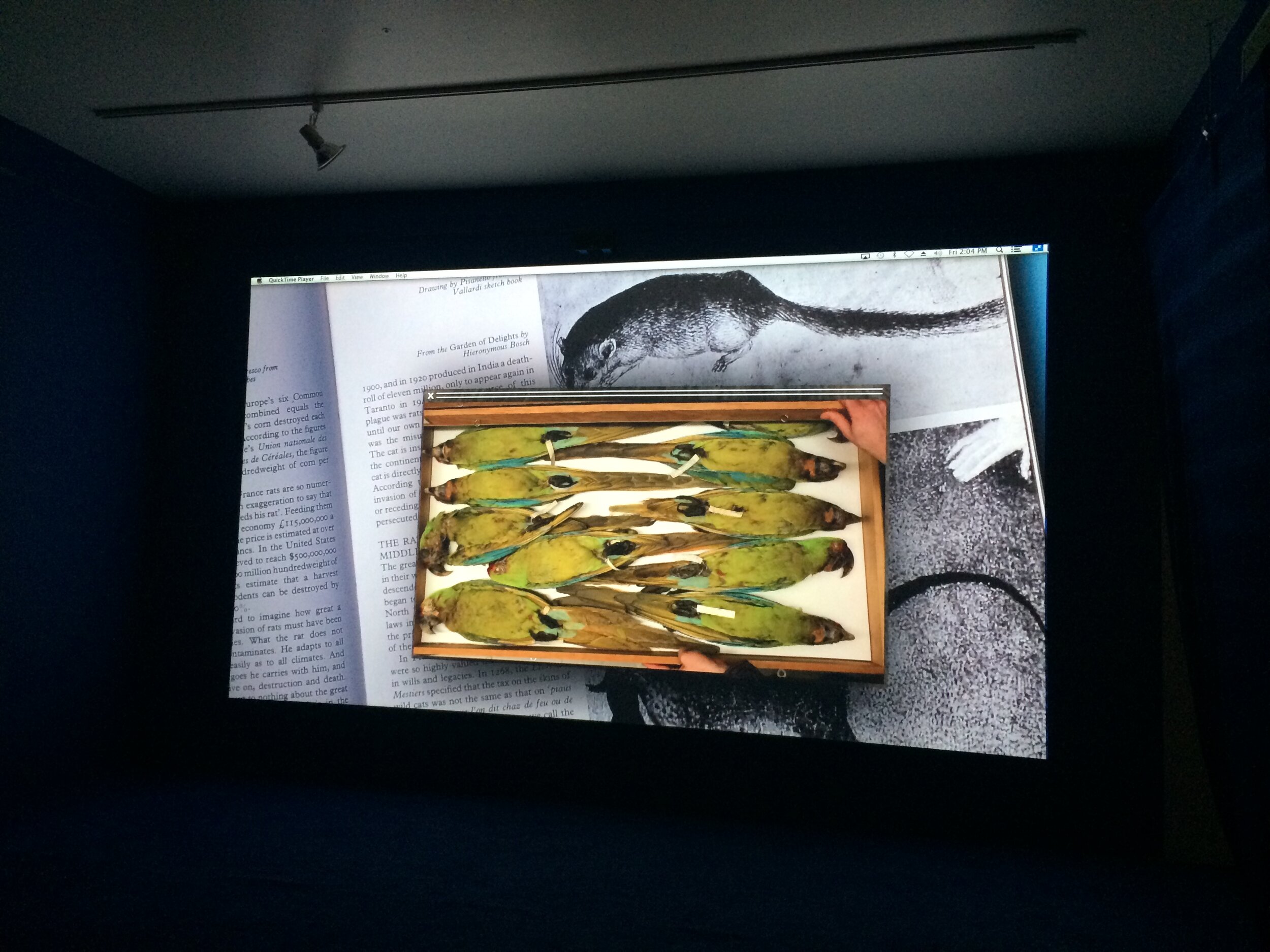

VII. A Battle and The History of The Universe

The 2013 Silver Lion prize winner and art world darling, acclaimed French artist Camille Henrot’s contemporary 13-minute epic ‘Grosse Fatigue’ is housed in a back room at the Maison of Longue Vue House and Gardens. The garden, established in 1924, is a world-class house museum surrounded by 8 acres of impeccably manicured grounds and was declared a historical landmark in 2005. It is an unlikely yet active location to add to Prospect.3’s sprawl and the viewing of this particular work.

Maison at Longue Vue House & Gardens. Image courtesy of ARC Magazine.

Henrot manages to create a tension in developing a re-imagined narrative that revises conventional typologies, taxonomies and histories, reinforcing a severe chronology that attempts to bring light and clarity to the complexity of our contemporary times. ‘Grosse Fatigue’ in its encyclopedic declaration starts at a click of the ‘History of the Universe’, and its rapid fire pace tells a story of categorisation, being and obsolescence.

The mania that ensued from its hyperawareness, a by-product of the search for order and the creation of disarray, links back to ‘The Search’ in Percy’s novel. Similarly, Henrot is on a search to further mythologise our present moment. She confronts us with a feeding frenzy, an audio-visual cornucopia exposing our Internet and Wikipedia savvy, marrying our times with various obsessions—creating a world that flattens our ability to differentiate, while highlighting the danger of a single perspective.

The soundtrack of ‘Grosse Fatigue’ is dark, melodious, drunk with rhyme. Composed by French DJ Joakim Bouaziz with a biting, poetic text co-authored by Henrot and Jakob Bomberg, the piece begins with the following:

“In the beginning there was no earth, no water—nothing. There was a single hill called Nunne Chaha. In the beginning everything was dead. In the beginning there was nothing; nothing at all. No light, no life, no movement no breath. In the beginning there was an immense unit of energy. In the beginning there was nothing but shadow and only darkness and water and the great god Bumba. In the beginning were quantum fluctuations.” – (Excerpt from Grosse Fatigue)

Henrot and her collaborators set up a new beginning for us to consider, one that uses multiple ethnographic and sociological associations, histories, cultures, philosophies and epistemologies to construct a viewing of a universe that is unknowable. What this exploration uncovers is the existential crises bound within contemporary, narrowed and essentialised truths, and our ability to consume creation’s narrative (antropofagia), invent new origins, timelines and, primarily, consciousness.

Camille Henrot, Grosse Fatigue. 2013. Installation at Longue Vue House and Gardiens, New Orleans. Image courtesy of ARC Magazine.

Grosse Fatigue is a vortex; it isn’t delicate.

I strolled through the French Quarter for an hour after the ribbon cutting ceremony which officially opened Prospect.3 to the public, complete with a second line parade through the district. The Quarter is the oldest neighborhood in New Orleans. Founded in 1718, it is now a National Historic Landmark. There have been two fires in the city’s history, and though both shifted boundaries and delineations of sections, the Quarter remains intact and static. Most of the Quarter’s current buildings date back to the early 1800s and is a mélange of French and Spanish style architecture that ends in a revelation of quaint streets, colourful surfaces and meticulous iron work on balconies and galleries.

I ducked in and out of several antique and craft stores to find postcards for a friend and make my way back to the park. We head to the New Orleans Museum of Art to witness Andrea Fraser’s live performance ‘Not Just A Few of Us’. Within the cramped and spilling theatre of the Museum, Fraser’s voice billowed promptly at 2pm as she launched into a stellar and dynamic delivery of a script based on an eight hour City Council meeting from 1991, brought to light by activist and civil rights advocate Dorothy Mae Taylor. Taylor proposed an ordinance to desegregate the private and mostly white exclusionary clubs that were the public face of Mardi Gras. Modern day Mardi Gras Krewes began in 1857 and was controlled by 4 elite associations, Momus, Comus, Proteus and Rex.

During Fraser’s performance she enacted several roles, throwing her voice and evoking accents and personas, moving between static pauses, crescendos and at times shouts. She brought to light the discourse surrounding hegemony, power structures and institutionalised racism that have pervaded the South. The audience was reactionary, engaging with Fraser’s appropriated rebuttals and making light of certain elements that critically engaged with the reality that is unfortunately still part of the American South. From the acquiescence and the confirmation of no Blacks participating in these public/private initiatives, to the sentiments that focused on equality, protection and cornerstones of citizenship, Fraser’s performance lasted for just under an hour and ended as sharply as it began, setting up a polemic with the ‘Other’ and the marginalised at the core.

VIII. A Death March: A Perfect Circle

The University of New Orleans (UNO) St. Claude Gallery hosted The Propeller Group in collaboration with Christopher Myers’ project ‘Shrine’, which comprises sculptural work by Myers and the debut of The Propeller Group’s 20-minute film ‘The Living Need Light, And The Dead Need Music’. The Propeller Group is a multivalent, multidisciplinary collective composed of visual artists from Saigon and Los Angeles. Phunam (Vietnam), Tuan Andrew Nguyen (Vietnam) and Matt Lucero (Los Angeles, CA) have been working together as independent artists, and use the collective to explore the making of ambitious projects. Teaming with Myers, they have unequivocally produced the pièce de résistance and the poetic epitome of Prospect.3.

The Propeller Group. The Living Need Light, And The Dead Need Music. 2014. Image courtesy of Lombard Freid Gallery and The Propeller Group.

With an embedded curatorial hope of determining the pivot of ‘The Search’ and hope for cultural exchange, the film—which takes its title from a Vietnamese proverb—is an assemblage that deals with history, ancestral worship and cultural syncretism, setting up a procession where community and familial bonds are idolised. Opening with synchronous shots moving through an alleyway in Saigon, the soundtrack reverberates through the walkway with a melody that is elegiac. The focal point rests on a teenage boy dressed in black, the subject of loss. The camera moves into his heart, and with a thump we are taken away from reality.

Here, we are greeted with a noisy and boisterous ceremony, populated by spiritual mediums, snake charmers, musicians, criers, performers and two main characters: the lead musician in the funereal brass band (the first echo of the mirroring of New Orleans as a site) and a seductive being, moving between modes of existence. We can assume that in this realm, she/he is a mirror and a stand-in for death. They burn money, set a ring on fire, dance wildly and sensuously, and sing a heartbreaking serenade while their body floats in a boat down a river, covered in a sheer fabric. We move through a procession that is dripping with spirit.

Speaking about the ritual and rite of passage, The Propeller Group states:

“In Vietnam, the history of the funeral wake, music, and processions that surround these ceremonies, is reflective of long traditions of ancestral worship. The purpose is not to bury the deceased, but to see them off on their journey to the immortal world and is usually expressed in uplifting and happy music as the coffin is carried to the tomb.”[4]

Grief never looked so evocative or so beautiful; the sweeping shots of the casket carried by bearers into the murky river; musicians playing syncopated rhythms out of sync; band members walking through deltas of rich mud; all of these things were too heartbreaking, too perfect and thus, too absurd for me to ponder. The perverseness of the beauty, its contemporaneity and openness felt shocking, as I had to confront the loss of my father, then and there in a room full of people, swallowed up by this powerful story. There was no escaping its seduction, the rich tropical hues of the country and river, the band playing hybridised instruments, and graves covered in coral vine or the Coralita, Antigonon leptopus, made it all the more impossible.

The Propeller Group. The Living Need Light, And The Dead Need Music. 2014. Image courtesy of Lombard Freid Gallery and The Propeller Group.

The Propeller Group. The Living Need Light, And The Dead Need Music. 2014. Image courtesy of Lombard Fried Gallery and The Propeller Group.

Time and space in ‘The Living Need Light, And The Dead Need Music’ is unimportant. We jump between wailing criers bending before a shrine adorned with an image of the dead flowers, incense and keepsakes given to the dead in order to help the transition from this life to the next. The landscape, body-scape, cemetery-scape and delta-scape reek of the tropics; the humidity alive on subjects’ bodies, the moisture and warmth loosening the fixtures of the spirits, enabling entrance into the trance procession where incantations are chanted, imagined.

The Propeller Group has a history with social practice. Their work has critiqued modern day capitalism, political regimes, practices and ideologies, systems of hegemonic control and the like. Here, the critique is still very apparent. The group created the gesture and the film “to celebrate the absurdity of uncles who died in Saigon and the United States during the Vietnam War.”[5]

With this mirroring of two cultures occupying the Global South—on a cultural technicality, New Orleans is in conversation with the Global South—there is a dislocation and fragmentation that reflects the notion of multiplicities, the possibility of many subjectivities, of being anything and nothing, a space that praises a type of spiritual and practiced liminality. The Propeller Group delivers a complex rendition of the past, present and future that coalesce into one plane for us to consume. The Group calls it the creation of a ‘Future Sound’, born between two cultures that have traversed centuries of violence and colonialism.[6]

The Propeller Group. The Living Need Light, And The Dead Need Music. 2014. Image courtesy of Lombard Freid Gallery and The Propeller Group.

In the end, ‘The Living Need Light, And The Dead Need Music’ is a celebration of cultural freedom and vestiges that continue to inform our daily experiences. It takes something personal (loss) and exposes it to communities, countries and regions with similar practices. As such, it opens up a rich dialogue to speak about inherited cultural remnants; and sometimes a deeper confluence where time, magic, the soul and science collide to create a suggestive volume that transcends normative cultural visualities and marries the private with public in practice.

IX. Ay, ay, a scratch, a scratch

Three days is but a scratch[7] on the surface of anything. I come from a 7 sq mile island, and every time I return I learn something new about it. A few days ago I was listening to an engineer speak about my father’s fear of doctors, something that I never knew. So much remains unknowable about our lives and the things and places we encounter. Hence I return to my savant, Solnit, who in her ‘Atlas of New Orleans’ points to its unfathomable and infinite qualities, and in summation, its innumerable versions.

It is pleasing to scratch and break the surface of any city. This city in particular in my mind and heart has always been so connected to the Caribbean as a crossroad and anchor. In a way, three days feel like cheating, it feels like I should conclude something real about this place, and that in itself is suspicious. Where a tabula rasa existed days ago, there is now a trace sediment on the glass of me knowing this place. Prospect New Orleans has lent to a greater knowledge of global consciousness, and if the success of P.3 is located in anything, it is squarely in this.

Sirmans has amassed a cultural medley of ideas, discourses, theories and practices that are fluid; pushing past the boundaries of typical representation, which has and continues to have dominion over much of the art world’s scope and vision—i.e. not every successful artist is a wealthy white male, and the oligarchy/patriarchy will one day tumble. To praise its diversity is to be condescending; to praise its stance and innovation against domineering museum practices that oftentimes exclude people of colour is patronising.

Prospect.3’s vision doesn’t discriminate, nor does it reaffirm the standard rubric advancing exclusionary art world practices. In fact, it comfortably supports a cross-cultural exchange in a way that feels organic, propitious and sine qua non. It is an act of (biennale/triennial) resistance that praises the central idea of highlighting and investing in commonalities, and searches to understand difference. The model challenges the canon, exposes its biases and as such is an indicator of very good things to come.