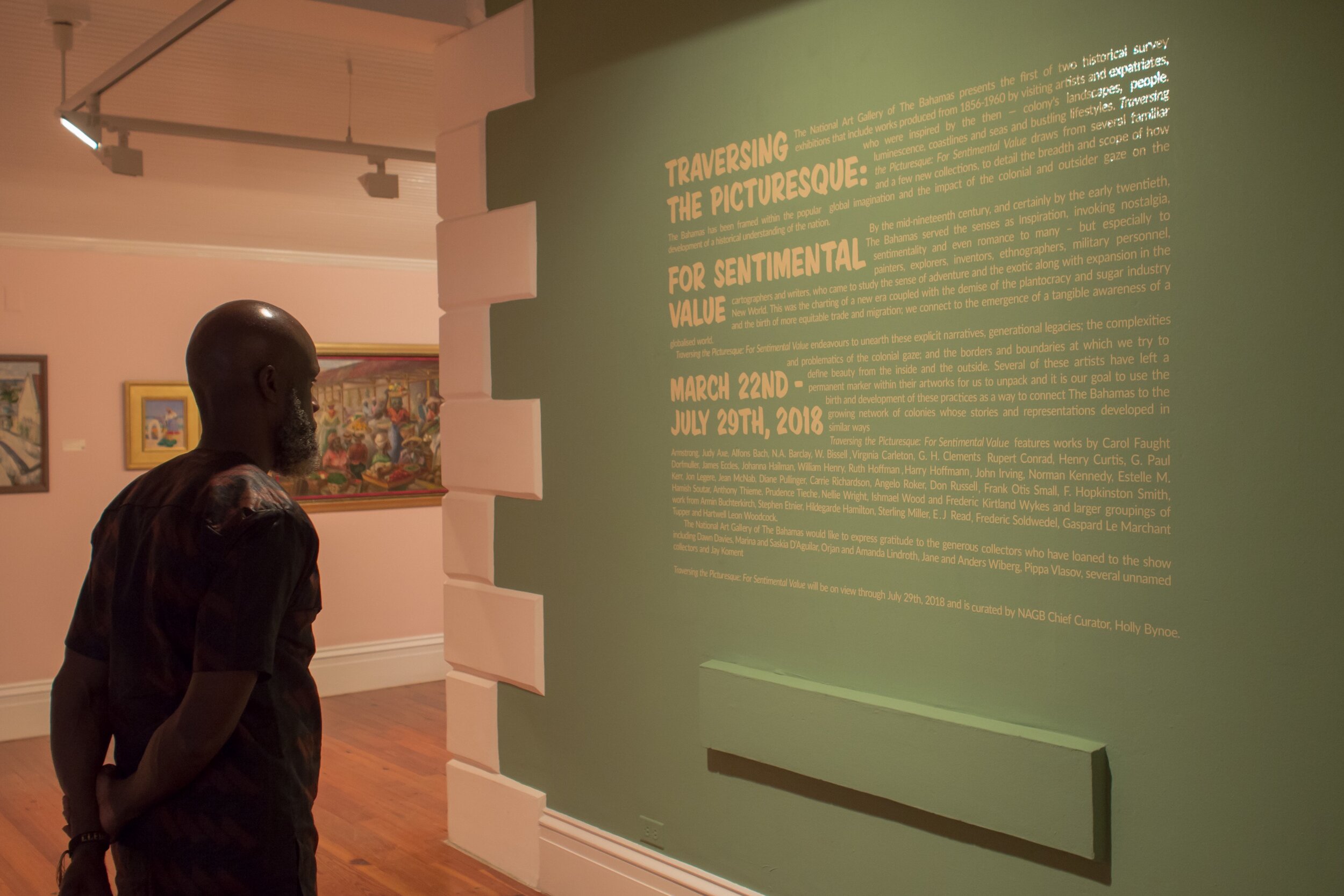

Traversing the Picturesque

For Sentimental Value

–

‘Traversing the Picturesque: For Sentimental Value’ is a historical survey that includes works produced from 1856-1960 by visiting artists and expatriates to The Bahamas, who were inspired by the then colony’s landscapes, people, luminescence, coastlines, seas and bustling lifestyles. In this overview, I detail how the birth and development of colonialist imagery continues to have a long-standing and far-reaching impact on the global continuation of the iconographic status of The Bahamas as a haven, a place of respite and paradise.

‘Traversing the Picturesque: For Sentimental Value’ is a historical survey produced at the National Art Gallery of The Bahamas in March of 2018, that includes works produced from 1856-1960 by visiting artists and expatriates to The Bahamas, who were inspired by the then colony’s landscapes, people, luminescence, coastlines, seas and bustling lifestyles. The exhibition examines the breadth and scope of how The Bahamas has been framed within the popular global imagination and the impact of the colonial and outsider gaze on the development of a historical understanding of the nation.

“By the mid-nineteenth century, and certainly by the early twentieth, The Bahamas served the senses as inspiration, invoking nostalgia, sentimentality and even romance to many—but especially to painters, explorers, inventors, ethnographers, military personnel, cartographers and writers, who came to study the sense of adventure and the exotic along with expansion in the New World.”

By the mid-nineteenth century, and certainly by the early twentieth, The Bahamas served the senses as inspiration, invoking nostalgia, sentimentality and even romance to many—but especially to painters, explorers, inventors, ethnographers, military personnel, cartographers and writers, who came to study the sense of adventure and the exotic along with expansion in the New World. This was the charting of a new era, coupled with the demise of the plantocracy and sugar industry and the birth of more equitable trade and migration; we connect this to the emergence of a tangible awareness of a globalised world.

From the New World: Impacts from the Outside and In

This advent, heralded by colonisation and the rise of the British Empire, was coming to a close with the end of slavery and Indentureship in the mid-1800s, opening up the belly of the Caribbean to an influx of stimuli. It started to attract significant players, within the arts and outside of it, who would come to transform how the region was seen from the outside, including those who visited The Bahamas and left essential bodies of work that positioned the Caribbean in a certain way. Artists like Winslow Homer 1836-1910 (American, working in The Bahamas circa 1885) and others came to redefine the region at the turn of the century, including Camille Pissarro 1830-1903 (St. Thomas, U.S. Virgin Islands) and Francisco Oller 1833-1917 (Puerto Rico) and of course the infamous French post-impressionist painter Paul Gauguin. Gauguin’s now influential mapping of an artistic ‘paradise’ during his visits to Panama and a four-month stint on Martinique in 1888 which would later frame and profoundly inform the work that he did in Southeast Asia, namely Tahiti, for which he is now infamous. He, like others, continued to be dazzled by the beauty of the islands and the richness of the motifs that were found in the landscape and the coastal areas.

The birth and idyll of the Caribbean as exotic, paradise and Eden were cemented during this time, and by 1920, the Caribbean became en vogue, continuing to be a muse to those in Europe. As the British Empire positioned itself to end the poisonous era of slavery, and with the United States and The Bahamas deepening its relationship, it is important to acknowledge the two critical historical moments that further shifted The Bahamas’ connection to the outside world. One in gargantuan ways and the other, entirely locally.

‘The Contract’ was a farm labour programme established on March 16, 1943, by the governments of The Bahamas and the United States of America. Under ‘The Contract’, from 1943 to 1965 an estimated 30,000 Bahamians, both men and women, migrated to the United States to work on short-term contracts. Initially, Bahamians were assigned to pick oranges in Florida, but as the programme grew, labourers traversed the United States, whether picking beans in Maryland, farming in New Jersey or working in agricultural packing and processing plants in New York.

Work was often hard, carried out in challenging climates and conditions and calling for long hours of manual labour. Additionally, Black Bahamian labourers who worked in the southern United States were met with ‘Jim Crow’ laws, which prescribed racial segregation in public. Nevertheless, Bahamians seeking to better their circumstance welcomed the opportunity to work, with nearly 5,000 participating in the first year of the programme.

This, coupled with the influx of artists who were fleeing Europe during persecution prior and during World War II, resulted in global upheaval which signalled a new era and centrally-focussed migration from Europe and the US back to Latin America and the Caribbean. It was at this time that famous writers came to live and work in The Bahamas— such as Ernest Hemingway and John Steinbeck—starting in the 1930s continuing through the late 1950s.

It is important to note that the Caribbean—mainly Martinique and Haiti given their département d'outre-mer (Outre-mer) and historical status—became a haven and safe ground to literary giants, including those from the Surrealist art movement in Europe. André Breton, the movement’s founder, travelled through the region and spent considerable time in Martinique with the intellectual luminaries Aimé and Suzanne Césaire, who would later become political vanguards in that territory. Adding to that, the work that they did together on the journal ‘Tropiques’ remains to this day an inspiration to artists and writers who considered the surrealism movement a deep political ideology.

Edna Manley. Negro Aroused. 1935. National Gallery of Jamaica.

Fast forward decades later to the post-independent Caribbean, and the legacy of Cesaire’s literary impact has shaped the Caribbean’s relationship to Black identity and, of course, gives us a more significant way in which we can parse through somewhat dated and at times problematic tropes connected to Black representation.

Wifredo Lam. The Jungle (La Jungla). 1943.

From this, the work of Wifredo Lam (1902-1982, Cuba), would have hardly found its place within the Western Canon with the creation of ‘The Jungle’ (1943), and the entree of Edna Manley (1900-1987, United Kingdom) into the Jamaican and regional lexicon as the matriarch of Jamaican Art is something that might have been contested, rather than both of them leaving indelible marks on our cultural space; giving credence to the region as a vital powerhouse of the genesis of art, art education and the rise of the visual art industry.

Vernacular

This timeline, alongside its historical interventions, is essential for the telling of how adventure, exchange, and the cross-flow of different movements and people continue the patterns of an already globalised world. In it, the Caribbean and The Bahamas is a significant component and contributor to this global narrative.

Broader to that, the significance of showcasing historical imagery and representations from the colonial era—early-18th century through mid-20th century—shows how the birth and development of colonialist imagery and representational works continues to have a long-standing and far-reaching impact on the global continuation of the iconographic status of The Bahamas as a haven, a place of respite and paradise.

The collection of works examines and rummages through the effects that the Bahamian landscape, as it was and as it was imagined, has had on a wide range of creatives (expatriates, emigrants and outcasts) that visited its shores, and those that made the islands their home.

While the collection is a mainly a survey of works pre-1960, before the Women’s Suffrage movement of 1962, it was crucial for us to fulfil the need to see how artists satisfied their desire to create, and thus we have given credence to eight artists who left considerable bodies of work for us to study, including Armin Buchterkirch, Stephen Etnier, Hildegarde Hamilton, Sterling Miller, E. J. Read, Frederic Soldwedel, Gaspard Le Marchant Tupper and Hartwell Leon Woodcock.

These reprieves will give us a moment to think about the development of genre painting, oeuvres, and the sense of how important historical documentation was to nation-building. We can critically reflect on how these representations of the landscape have had lasting effects on Bahamians’ relationship to slavery, emancipation, the wave of new industries including the maritime and trade industries—pineapples, sisal and sponges—and the transformative move to modernity.

In conjunction with the later trend of Realism, we see a more in-depth look at the coastlines and the architecture of a marinescape. We also see how intrinsic and important it was to witness the shift from the popularity of tropical and exotic imagery, to investigations into landscapes and gardens, providing an invaluable artistic and historical record of the nation and its constituents at the turn of the 20th century. Most of these views are long since gone from the current experience in Downtown Nassau, as well as the island of New Providence as a whole, where vistas are now obliterated and obscured by development.

On a subtler and more nuanced level, it also shows how the circulation and consideration of European art and its styles (notably Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, Romanticism and Expressionism) impacted upon and continues to thoroughly influence the makeup of contemporary Bahamian practice, most notably in the works of Eddie Minnis, Dorman Stubbs, Ricardo Knowles, Alton Lowe and R. Brent Malone. It has served as a cornerstone on which many representations of the Caribbean, and certainly The Bahamas, was built.

These reworkings of the landscape and people continue to provoke new renderings and understandings of The Bahamas’ national development. Each pause will advance and provoke thoughts on our current independent moment, deepening the impact and importance of the genesis and evolution of contemporary art practices, reclamation of our own narratives and decoloniality.

‘Traversing the Picturesque: For Sentimental Value’ endeavoured to unearth these explicit depictions and associated generational legacies; the complexities and problematics of the colonial gaze; and the borders and boundaries at which we try to define beauty from the inside and the outside. Several of these artists have left a permanent marker within their practices for us to unpack, and it is our goal to use the birth and development of these practices as a way to connect The Bahamas to the growing network of colonies whose stories and representations have developed in similar ways.