From a Daughter of the Soil

A part of work as Generator for The Hub Collective, this decolonial story of Bequia's ripe history starts with a look into the Indigenous Era, moving through the vagaries of the colonial battle for the Grenadines. Starting with piracy, the Black Carib uprising against the British and French and early settlements, we move through the rise of the whaling industry and our creative sea faring resilient culture.

With special edit assistance from Jessica Jaja. Photographs by Jessica Jaja, Anusha Jiandani, Akley Olton, Judy Simmons’ archive and other archives.

Image of Toco’s in Paget Farm. Image by Anusha Jiandani.

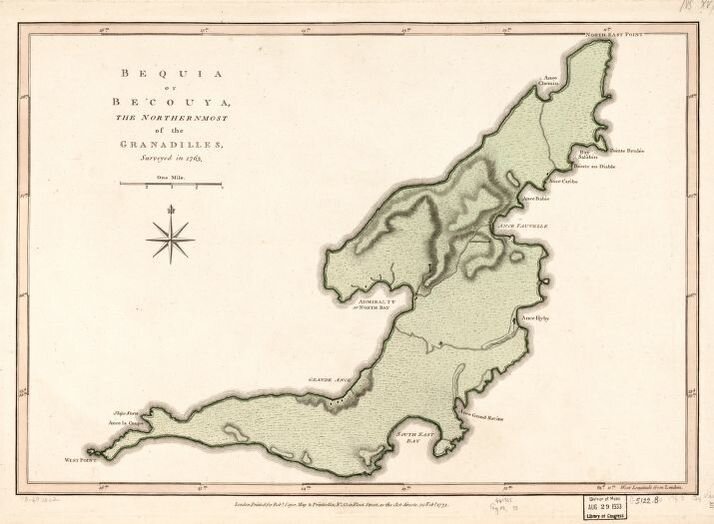

Our island, Becouya, “Island of the Clouds”, historically was noted to be “too inaccessible to colonise,” and was one of the last islands to be settled by Europeans in the Lesser Antilles [1]. The island's lack of surface water and springs as well as its shortage of arable land appear to have been major deterrents to early settlement.

The Before Time: Our Indigenous Era

Bequia is believed to have been discovered and inhabited as long as 7,000 years ago by Indigenous hunter-gatherers, the Ciboney [2] people, who came in small crafts from South America. They were displaced by the Arawaks who were migrating north through the region [3]. The Ciboney people went on to settle other countries in the Greater Antilles, especially Cuba, Haiti and the Dominican Republic.

The Arawaks, who originated in the Orinoco Basin area of South America and migrated northward throughout the Antilles, were a peaceful people and were very accomplished at pottery and agriculture [4]. They practiced slash-and-burn cultivation of cassava and corn, recognised social rank and gave great deference to theocratic chiefs. Their beliefs centred on a hierarchy of nature spirits and ancestors, paralleling somewhat the hierarchies of chiefs. They were the first to settle Bequia, finding haven and home using the island's natural resources of land and the sea to survive.

The Arawaks left their material culture buried in our soil, contents of which are still coming to our consciousness today. Barbadian historian Dr. Karl Watson, during his time as editor of the Journal of the Barbados Museum and Historical Society, shared an account of a visit to Bequia after Hurricane Ivan, circa 2004/5:

Formal excavation would do much to further our knowledge and understanding of the successive occupations of Bequia by groups of Arawaks distinguishable by their differing ceramic styles. Also, by compassion with provenanced collections from other Eastern Caribbean islands, our understanding of the migration routes and socio-economic links of the pre-Columbian populations of our islands would be greatly enhanced. Even a cursory examination of the Bequia collection reveals obvious stylistic relationships between the ceramic traditions of Bequia and those of Barbados. This is especially true of the early Saladoid material culture. The sherds [5] found on Bequia show that the site was occupied by Saladoid, Barrancoid/Troumassoid and Suazoid groups and can be compared to the Port St Charles and Spring Garden sites in Barbados [6].

This is important to understand as our Indigenous ancestors laid a foundation of creativity, sustenance and community for us to ground ourselves in and there is not much more waiting in the annals of our country’s history to explore. [7]

According to archeologist Margaret Bradford it is quite possible that the Park Point site previously noted by Watson “could have been inhabited by people who produced Saladoid/Barrancoid series pottery somewhere around A.D. 300, or at the latest, A.D. 500. These dates are substantially earlier than the A.D. 1200 date which the Bullens’ (1972) suggested for this site. [8]

While the studies of our island continue to evolve and new material emerges on our history and archeology it is clear to see that before the Europeans came to the New World there were healthy civilisations of Indigenous peoples who called Bequia their home.

Fig. 1: The St. Mary’s Anglican Church and compound in Port Elizabeth. The church was established in 1829, and was rebuilt after damages caused by a hurricane. The compound currently houses The Hub Collective Inc. Image courtesy of Judy Simmons’ Island Life Stories.

A Brief History of a Violent Kind: The Colonials Fight It Out

Given the peaceful nature of the Arawaks, they were later displaced by the Caribs around 1400 AD who settled various islands including St. Vincent. When European colonists traveled through the Southern Caribbean region in the late 15th century, it was the Caribs that they first encountered.

Prior to 1660, when the Caribs revolted against French rule, the Governor Charles Houel du Petit Pré [9] of Guadeloupe retaliated with war against them. Many Caribs were killed and those who survived were taken captive and expelled from the island. On Martinique, the French colonists signed a peace treaty in 1660 with the first peoples of our islands. Some Caribs fled to St. Vincent, where the French agreed to leave them at peace. [10] In 1664, France laid claim to Bequia, but did not establish a permanent settlement there. [11]

Fig. 2: Obelisk/monument to St. Vincent and the Grenadines' only national hero, Joseph Chatoyer, Paramount Chief of the Caribs. The monument is located at Dorsetshire Hill where the Carib Chief was murdered. Image by Akley Olton.

In 1675, the slave ship Palmyra sank off the coast of Bequia. The enslaved, newly freed Africans who managed to swim ashore eventually mixed with the native Caribs to form the "Black Caribs," ancestors of the Garifuna people. [12]

Planter, slaver and President of the Commission for the Sale of Lands in the Ceded Islands, Sir William Young, notes in his accounts that the Palmyra was carrying slaves that were a “warlike Moco tribe from Africa.” Rev. C Jesse recounts “A ship laden with African Negroes destined for the West Indian slave market foundered on reefs to the Windward of the island (Bequia).” The captives [13] who succeeded in getting ashore were relieved kindly by the Amerindians who then occupied Bequia, and eventually intermarried with them. Their descendants, who remained more of the African pigmentation than of the Amerindian, came to be known as the Black Carib. At times they proved to be a source of trouble to their fairer-skinned relatives, the Yellow Carib, also to the English and the French. [14]

It is important to acknowledge in the reading of this history that the terminology of Carib is one that is very contentious given power differential of the coloniser and the eventual genocide of Indigenous peoples of the region and the rise of the plantocracy.

Kim shares “The classification of the indigenous peoples of the Caribbean including St. Vincent, has been a long standing problem in fields ranging from history and literary studies to anthropology and archaeology. Although most colonial and present-day accounts of St. Vincent use the term Carib to indicate the ethnicity of the Amerindians who fought against British rule, the name is an invention of early Spanish explorers and administrators, who divided the peoples they encountered in the Caribbean into two groupings of Arawak and Carib to distinguish friendly from hostile natives. Any groups considered hostile were deemed Carib and troped as cannibals, a term that itself derives from Carib. [15]

These namings and designations clearly show early colonials attempts of ethnic mapping and territorial conquest. It was more than 200 years before the Europeans gained a foothold, as the Black Caribs had a well earned reputation for repelling invaders to their shores.

We will circle back to the story of the Black Caribs and the Garifuna people below.

Fig. 3: Jefferys, Thomas, -1771, and Robert Sayer. Bequia or Becouya, the northernmost of the Granadilles. London, Printed for Robt. Sayer, map & printseller, 1775. Map. https://www.loc.gov/item/73697202/.

Bequia’s Safe Haven: Admiralty Bay and Blackbeard

In 1717, as piracy gripped the region, Bequia became a well-established watering hole and source of lumber for visiting vessels, including buccaneers, privateers and pirates. [16] Our island - which couldn’t sustain much agriculture - was filled with the native tree species white cedar, Tabebuia heterophylla; the perfect timber for the production of boats, schooners and marine vessels. This abundant species kept on attracting explorers of all kinds including the notorious and much feared pirate, Edward “Blackbeard” Teach. [17]

Teach seized the slave ship “La Concorde” which was on her way from Africa to Martinique. Teach and his crew raised sails and conquered the slave ship with the enslaved and began converting La Concorde in the heart of Admiralty Bay into the iconic Queen Anne’s Revenge, the most powerful warship in the Americas at the time. [18] This is one of the first recordings of careening and salvage on our island.

Resisting By Any Means Necessary: The Great Genocide

In 1719, tensions rose so high that the “Yellow” Caribs united with the colonial French against the Black Caribs in what is called the First Carib War. The First Carib War (1769–1773) was fought over British attempts to extend colonial settlements into Black Carib territories, and resulted in a stalemate and an unsatisfactory peace agreement. Led primarily by Black Carib War Chief Joseph Chatoyer, [19] the Caribs successfully defended the windward side of the island against a military survey expedition in 1769, and rebuffed repeated demands that they sell their land to representatives of the British colonial government. [20]

Fig. 4: Wall Murals by New Roots in the Paget Farm community of Bequia. Image courtesy of Anusha Jiandani.

The Black Caribs ultimately retreated to the hills but continued to resist the Europeans, while the French established plantations and imported African slaves to work the fertile land. [21]

After the Treaty of Paris in 1763, [22] St. Vincent and the Grenadines was ceded to the British and became a part of the expanding British colonial empire. France re-captured Saint Vincent in 1779 during the American War of Independence, but it was restored to Britain by the Treaty of Versailles in 1783. In 1795, [23] the Carib resistance grew and reached a boiling point on March 14th, when a battalion of British soldiers, led by General Ralph Abercromby, marched toward Dorsetshire Hill. That night, Chief Chatoyer [24] was killed by Major Alexander Leith, and although the rebellion continued until June 1796, Chatoyer's death led to the desertion of the French supporters and turned the tide of the war. [25]

Approximately 5080 Caribs [26] (most Black but some Yellow/Red Caribs) were deported from Saint Vincent to the island of Baliceaux, off of Bequia in October 1796. [27] Here they were overseen by the British military forces where half of them died in concentration camps from famine, outbreaks of yellow fever and other infectious diseases. The ones who survived, numbering 2,248 were sent to the island of Roatán off the coast of present-day Honduras, where they later became known as the Garifuna people. [28]

The story of the island of Balliceaux, although subject to a different form of historical processes and events to other Caribbean islands, broadly mirrors this tripartite structure: a place of pre-contact settlement, a place of genocide, a place of memory and memorialisation. [29]

The landscape of the small island off of the Eastern coast of Bequia is now forever changed with this sordid and tragic history. As a sacred heritage site is a space of significant import for those who identify as Garifuna in the diaspora along with descendants in our country. The lack of acknowledgement to memorialise the space or to turn it into an official memorial site can be seen as another kind of warfare on Garifuna people globally.

Since 1899, Balliceaux is privately owned by the Linley family and they have put the island, along with Battowia, a 151-acre island located nearby for sale and are asking for US$27 million for both islands [30]. Dr. Yanique Hume, a lecturer in the Department of Cultural Studies, at UWI’s Cave Hill Campus in Barbados in 2018 during the 5th International Garifuna Conference in Kingstown noted that Balliceaux “can become the central ground through which sequestered history can enter into public discourse and debate, through reimagining and branding specific locales as unique heritage sites that allow one to experience spaces in more profound ways.” [31]

Fig. 5: View from the eastern facing harbour of Balliceaux looking on to Battowia. Sept 2020.

We hope in the near future that Balliceaux can elevate to become a sacred pilgrimage site where descendants and Garifuna people can grieve, make new memories and connect to the land in order to venerate their/our ancestors.

A Melting Pot: Not of Sugar, Other Things

As Bequia’s cultural make up shifted during the early 18th century pre-emancipation period, the island became the meeting ground for other settlers across the Caribbean, namely those from Martinique, St. Kitts and Saba. They comprised the enslaved, planter-class, merchants, mariners, boat builders (who brought, in particular, schooner knowledge from St. Kitts) [32] and others who provided new intel about water harvesting to Bequia.

Islands like Saba and the knowledge incoming from its people informed a large part of our traditions and surnames like Hassell turned into Hazell [33]. According to Bequia historian Nolly Simmons, Saba is the ancestral ground of a significant part of the population of Bequia [34]. The “Saybees” as they are now referred to left a blueprint for our evolution and our connection to the sea which continues to evolve to this day despite challenges around the loss of traditional and Indigenous knowledge.

Bequia became a space for the production of sugar, cotton, indigo and cocoa, while the sea and maritime livelihoods became stronger and central to the narrative of our ancestors. The enslaved made up the most significant portion of the population, over 85%, [35] and to this day African knowledge continues to proliferate, expanding and influencing our coding, cuisine, language, habits and dreaming.

Fig. 6: Remnants of the main structure of a Lime Kiln, perhaps the only one of its kind in the Eastern Caribbean. This is also known as Middle Ring, which is located in Paget Farm just outside the entrance to the Bequia airport. Image by Anusha Jiandani. Thanks to Herman Belmar for revisions to the captions.

British planters pushed ahead with sugar cane cultivation on large estates across the island and in 1827, Shephard listed nine sugar cane estates in Bequia, ranging from 105 acres to 1,000 acres. In the same year, the island had 1,257 slaves. Aside from slave villages and plantation houses, the only settlement was Bequia Town (now named Port Elizabeth) which served as the island's administrative and trading centre. [36]

In addition, according to scholar and researcher Margaret Bradford in her article Investigation of Historic Bequia Lime Kilns she shares “The ruins of three historic lime kilns on the island of Bequia were investigated. The kilns were used to burn coral to make lime for mortar and plaster which were used in 18th and 19th century building construction. Lime was also an essential element in the manufacture of sugar.”

In the 18th and 19th centuries, lime mortar and plaster were used to construct the durable stone buildings required by a booming plantation industry on Bequia. Lime was also added to the cane juice during the boiling process to clarify it. Although the 17th century sugar refining recipe isn’t known, today’s processing requires an average of 7.7 pounds of lime per ton of sugar produced (Singleton and Birch).

Bequia’s planter class encountered serious environmental restrictions on the cultivation of sugarcane, namely the lack of rainfall and the shortage of gently sloping land. The marginal plantation agriculture was ill-equipped to survive the freedom that came to the enslaved via the Emancipation act in 1838.

“The unsuccessful planters mostly returned to England or moved on, while those who remained - a greatly diminished population of no more than about 700 people most of whom were former plantation workers [37] - were forced to seek new ways to make a living.” [38]

After emancipation and the mass exodus of the planter class on the island, more land was devoted to subsistence farming and to livestock rearing. Sharecropping became the most important land tenure system on Bequia, as it guaranteed that tenants could retain a percentage of crops. Tenants were also able to earn wages for work, but costs were often too expensive for the planter class to afford.

The plantation workers settled in discrete areas of the island; sharecroppers occupied the land in Lower Bay, while in Hamilton African slaves settled and remained relatively isolated. [39] The population turned to shipbuilding and fishing as a primary activity, but in the 1850s Yankee whalers began to pull into Admiralty Bay for repairs, and in many cases took on locals for crew. [40]

This fleeing led to emigration from Bequia, leaving the resident population relatively free to develop its own Creole culture without many elite whites. Somewhat isolated, the Grenadines populations developed strong, separate identities and customs that fueled suspicion from the larger, dominant islands of which they were political dependencies. [41]

BLOWSSSSSSSS

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Yankee skippers recruited West Indians to fill their crews, as it became increasingly difficult for them to find American seamen to go whaling. [42] Whalemen from New England chased, killed, and processed humpbacks near the Windward Island settlements, affording the local populations an excellent opportunity to observe whaling activities. Moreover, whaling ships made frequent visits to Windward Island ports in order to replenish their stores. It was through these contacts that New England whaling technology was introduced to the West Indies and to Bequia.

Within the South-Eastern Caribbean, whaling centres of varying size and scale were established in Barbados, St Vincent and the Grenadines and also at Pigeon Island, St Lucia, Glover Island, Grenada and Prince Rupert’s Bay, Cabrits, Dominica. [43] The first and most important whaling centre was on Bequia. Whaling not only brought much needed income to the island but the activity also played a major role in the transformation of the island from a land to sea-based economy. [44]

Fig. 7: Monument to Paget Farm’s whaler men, past and present on whale bone. Drawings by New Roots. Image by Anusha Jiandani.

In the 1850s, Great Elder and the pioneer of Bequia whaling, the then young William "Old Bill" Thomas Wallace adventured to Boston to learn as much as he could about the industry and skill. Returning to the island, this “Yankee Whaling” [45] knowledge spread like wildfire through sourgrass and bramble, thus our world-class boat building traditions emerged.

Old Bill returned with ideas around design techniques and whaling in the tropics, and began adapting his boat building inspired by the model of the Massachusetts whaling schooner.

“The Iron Duke” and “Nancy Dawson”, the iconic double-enders, started off this journey. While the year is uncertain, it is believed that Old Bill started whaling in 1875 or 1876. [46] It was noted in trade logs that years before in 1867 a considerable quantity of whale and Blackfish oil were exported due to Yankee whalers kickstarting the export and trade industry in Southern Caribbean and in particular St. Vincent and its dependencies, the Grenadines. From 1867 through 1870 inclusive, 6.702 barrels and casks of whale oil - amounting to over 250,000 gallons and valued then at 28,000£ - were exported. [47]

Fig. 8: The Iron Duke in Port Elizabeth. Some elements of the first whaling vessel in Bequia from 146 years ago remain intact. The Iron Duke is currently undergoing repairs.

Designed for whaling, fishing and inter island trading, these boats brought Bequia into the global spotlight and transformed our small island into a bustling trade hub.

Fig. 9: Boat building continues to present day. Image by Anusha Jiandani.

Interesting fact, our Bequia holds the record for building the largest wooden vessel in the Lesser Antilles, the 165-foot three-masted infamous Gloria Colita. She weighed a whopping 175 tons, and this legendary vessel came into the world with a bang and went out in mystery:

During a mysterious voyage in May of 1941, Captain Reginald Mitchell loaded rice in British Guyana (Bee Gee) bound for Havana. There he loaded sugar and went to Venezuela. Once in Venezuela, he discharged his entire Bequia crew and signed on a Spanish speaking crew. From there, they sailed to Mobile and loaded lumber destined for Havana, Cuba.

After they left Mobile, they were never heard from again until a United States Coast Guard plane sighted the Gloria Colita awash, drifting in the Gulf Stream with no sign of life on board. She was eventually towed back to Mobile and sold to an American for scrap. No trace or word was ever heard of Captain Reg Mitchell or his crew and the story of the Gloria Colita drifted into Caribbean folklore where her legend and that of her seven-foot captain have continued to grow ever since. [48]

Read more about the mysteries of Captain Reg and Gloria Colita here and here.

Fig. 10: Launching the Gloria Colita in 1939 in Port Elizabeth, Bequia.

But we digress, moving back to 1875 when the whaling industry started to gain traction after Old Bill returned to Bequia and set up whaling "companies" consisting of four whaleboats and about 26 men per company. This brought new industry, export, trade possibilities, warriors, talents and sea faring guardians to our shore.

Fig. 11: See Gloria Colita’s ruined remains in this news account.

“Bequia emerged as the center of Caribbean whaling and from this entrepôt, the model of shore-based whaling stations targeting mainly humpback whales spread to at least 11 islands throughout the region.” [49] [50] [51]

Artisanal and traditional whaling of humpbacks has been covered in many stories, publications, journals, articles and recently there has been a call to halt this tradition by many environmentalists as it is seen as not practiced by Indigenous or Aborginal Peoples. A decision was reached in 2013 when the International Whaling Commission (IWC) limited the quota to four whales a year. [52]

Fig. 12: Semple Cay as seen from the village of La Pompe, the current location of the Whaling Station where Bequians gather to celebrate the ritual of the hunt. Image by Anusha Jiandani.

Resources to know more about Bequia’s whaling history include:

Artisanal and Aboriginal Subsistence Whaling in Saint Vincent and the Grenadines (Eastern Caribbean): History, Catch Characteristics, and Needs for Research and Management

Tom Weston’s documentary: The Wind That Blows

Footage of the “Iron Duke”

A tribute to Athneal Ollivierre by Horace Beck

Local perspectives and debates on Whaling on Bequia

Bequia’s Whaling History

More on Atneal Ollivierre: here and here

History from the International Whaling Commission

J Gool sings “Athneal was the greatest whaler man” as part of the participatory film project “Reclaiming Paget Farm”

Learn more about Joseph “Pa” Ollivierre here.

To and from Bequia

Around that same time there was a mass exodus given the post emancipation proclamation and the abolition of slavery, of “poor whites” from Barbados to the Windward Islands. Barbadian historian Dr. Karl Watson cited, “As many as 400 poor white Barbadians had settled in St. Vincent and another 100 had been sent to Bequia...and estimated that “between 1860 and 1870 some 600 and 700 poor whites left Barbados to settle in the Windwards”. [53]

This settlement of poor whites aka “Redlegs” changed the social, economic and cultural make up of Bequia with a considerable settlement being established in Mt. Pleasant, and another in Dorsetshire Hill on the mainland of St. Vincent. The members of the poor white or ‘Bajan’ community as they are more commonly known, traditionally connected to subsistence farming as they worked and witnessed from the fringes of the plantation.

Fig. 13: The Gooding and Davis family, descendants of the “poor white” population that migrated and settled in Mt. Pleasant in the 1860-1870s. Image circa mid 1950s.

For historical context, the Redlegs are descendants of Scottish and Irish people who settled Barbados in the 17th and 18th centuries. Some were innocent people who were rounded up from across the country by teams of Oliver Cromwell’s “man-catchers”, bound in chains and shipped to Barbados to work on sugar plantations. After Emancipation when slaves were freed, the Redlegs left, or were evicted from their plantations. The majority settled the St. John parish of Barbados. When they left Barbados and settled on Bequia they became engaged in farming but also found the landscape and conditions hostile. [54]

The men learned carpentry, ship building and sail making from the mariners on the island. In the early 20s a lot of them worked in the US and sent remittances home to build trading vessels. At that time, every family had shares in two-masted schooners, which were operated by the family heads and their sons. [55] This tradition is still very much alive and well in Bequia today.

Repelled by unproductive soil and the lack of remunerative employment on land, an increasing number of Bequians left the island in search of work elsewhere. Emigration was directed mainly to English-speaking countries and colonies in the Western Hemisphere. [56] Throughout the late colonial period, the major destination of Bequians was Trinidad, which received heavy immigration from all British Windward Islands from the middle of the 19th century until its passage of strict immigration laws in 1959. [57] Aruba and Curacao employed scores of Bequians in the oil refineries in the 1920s and 1930s, and many worked as seamen on oil tankers operating out of Lake Maracaibo, Venezuela, during the Second World War. After the War, a small, but steady stream of Bequians left for England and then to Canada. The United States was also a recipient of Bequia Islanders, most arriving in the 1920s and since 1965. [58]

For more information on how the poor white community was understood in Barbados read Dr. Matthew C. Reilly’s “Archaeology below the Cliff: Race, Class, and Redlegs in Barbadian Sugar Society”, [59] which is the first archaeological study of the poor whites of Barbados, the descendants of seventeenth-century European indentured servants and small farmers.

Spirit Island: Our Essence Continues

The amalgamation of farmers, sea faring people, boat builders, artisans, intellects, whale hunters, story tellers, pirates and medicine people from various cross sections of the world including various tribes of Africa, the Indigenous peoples of Mesoamerica and South America including the Amerindians of which there are several identifications including Kalinago, Carib, Garifuna - the early settlers from France and the French West Indies, along with the English followed by the mid-nineteenth century arrival of the Irish and Scottish settlers gave shape to the big spirit of this small land.

Fig. 14: Youth playing on fishing boats in Paget Farm. Image by Anusha Jiandani.

Life in Bequia continues to evolve and as the nation enters into its fourth decade of post-independence [60] realities, we now have a significant population of global expatriates who have decided to make Bequia their home. Bequians and Vincentians began to disperse globally from the early 1910s with the advent of World War 1 until today. Our diaspora continues to be one of our largest supportive and reparative communities.

Today, tourism, trade, fishing, micro-cottage industries and small business entrepreneurship shape the everyday realities of our island in the clouds. Becouya remains a place of spirit and essence sustaining the curious, misfits and creatives.

At The Hub, we are tapping into the wisdom of our great great grandmothers and fathers, our ancestors, and their cunning to remember and to do.

Fig. 15: Cemetery in Paget Farm/Gelliceaux, Bequia. Image by Anusha Jiandani.

Notes

Adams, John Edward. "Historical Geography of Whaling in Bequia Island, West Indies." Caribbean Studies 11, no. 3 (1971): 55-74. Accessed August 29, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25612403.

Ciboney, also spelled Siboney, Indian people of the Greater Antilles in the Caribbean Sea. By the time of European contact, they had been driven by their more powerful Taino neighbours to a few isolated locales on western Hispaniola (Haiti and the Dominican Republic) and Cuba.

https://caribbeanmassive.tumblr.com/post/14101364582/human-life-on-bequia-dates-back-thousands-of-years

History of the Arawak people. Accessed on September 1st, 2021: https://www.britannica.com/topic/Arawak

A sherd is a broken piece of pottery with edges that are sharp, usually referring to one that is found in an archaeological site. In essence, the words shard and sherd are interchangeable, though the term sherd is favored by archaeologists. Sherd is an abbreviation of the word potsherd, which has been in use since the 1300s.

Karl Watson. Surface Collections from an Eroding Midden on Bequia, St. Vincent and the Grenadines. Journal of the Barbados Museum and Historical Society. Vol. LII. December 2006

Ripley P and Adelaide K Bullen, Archaeological Investigations on St. Vincent and the Grenadines West Indies.. https://ufdc.ufl.edu/CA01200017/00001/54j

Margaret Bradford. Reassessing Chronology: A Ceramic Analysis on Bequia. Accessed on: https://ufdcimages.uflib.ufl.edu/AA/00/06/19/61/00637/16-53.pdf

Governor Carles Houel: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Hou%C3%ABl_du_Petit_Pr%C3%A9

The Caribs resisted French settlement with equal vigour, until a peace treaty (1660) with them permitted European settlement: http://web.simmons.edu/~chen/GDL/Group/martin~1.htm

See history here: https://h2g2.com/edited_entry/A579053

The Black Caribs “Garifuna” originated on St. Vincent Island, in the West Indies, as a cultural and biological amalgam between Amerindians “Arawak and Island Caribs” and West Africans. A total of 2,026 of the Black Caribs were deported by the British in 1797 to the Bay Islands, from which they further emigrated to Honduras, Central America.

Young, WIlliam. “Account of the Black Charaibs in the Island of St Vincent's

Jesse, Rev. C. "A Note on Bequia: Cradle of the Black Carib." <i>Caribbean Quarterly</i> 3, no. 1 (1953): 55-56. Accessed September 4, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40652561.

Kim, Julie Chun. "The Caribs of St. Vincent and Indigenous Resistance during the Age of Revolutions." <i>Early American Studies</i> 11, no. 1 (2013): 117-32. Accessed September 4, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23546705.

Info on Teach’s history in Bequia: https://www.bequiatourism.com/blackbeard.pdf

Edward Teach, better known as Blackbeard, was an English pirate who operated around the West Indies and the eastern coast of Britain's North American colonies.

Mark Wilde Ramsing’s Historical background for Queen Anne’s Revenge Shipwreck Site. https://digital.ncdcr.gov/digital/collection/p249901coll22/id/696099

Joseph Chatoyer, also known as Satuye, was a Garifuna chief who led a revolt against the British colonial government of Saint Vincent in 1795. Killed that year, he is now considered a national hero of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, and also of Belize and Costa Rica.

The First Carib War: https://military.wikia.org/wiki/First_Carib_War

ibid.

In return, France recognized the sovereignty of Britain over Canada, Dominica, Grenada, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, and Tobago.

More on the Second Carib War: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Second_Carib_War

Biography on Joseph Chatoyer. https://alchetron.com/Joseph-Chatoyer

ibid.

Bullen, R.B., & Bullen, A.K. (1972). Archaeological investigations on St. Vincent and the Grenadines, West Indies. William Bryant Foundation, American Studies, Report No. 8. p.40

Gonzalez, N.L. (1988). Sojourners of the Caribbean: Ethnogenesis and ethnohistory of the Garifuna. University of Illinois Press. p.35.

Anderson, Alexander. Anderson’s Geography, 94.

Niall Finneran and Christina Welch. Mourning Balliceaux: Towards a biography of a Caribbean island of death, grief and memory. Island Studies Journal.

UWI lecture proposes a model for tourism in Balliceaux. Accessed: https://www.iwnsvg.com/2018/03/14/uwi-lecture-proposes-model-for-tourism-in-balliceaux/

Ibid.

Niall Finneran. Slaves to Sailors: Afro-Caribbean maritime archaeology. University of Exeter, African Archaeology Research Day 30 November 2016.

“In Memoriam Hercules Hazell who died in September 1833 at the age of 84 years, and Elizabeth his wife, were among the early settlers in this island. Their son, Hercules Hazell died in September 1848, aged 63 years and with his parents is buried in this churchyard. https://ancestors.familysearch.org/en/L149-RGM/hercules-hazell-1749-1833

The Saba Islander by Will Johnson: https://thesabaislander.com/2016/07/16/to-the-island-of-bequia/

By 1829, Bequia boasted nine sugar plantations of between 100 and 1000 acres, numerous smallholdings growing mainly cotton, its own new church and a close-knit population of maybe 1400 people, of whom at least 1200 were enslaved labourers. But the island's prosperity from sugar was short lived: 1828 was the peak of production of sugar in these islands. Source, Bequia Tourism.

Adams, John Edward. "Historical Geography of Whaling in Bequia Island, West Indies." Caribbean Studies 11, no. 3 (1971): 55-74. Accessed August 29, 2021.

Note well, that the reference here is to enslaved Africans or slaves, who weren’t workers but unpaid labourers that suffered for centuries under the plantocracy.

Excerpted from Bequia Tourism’s website: https://www.bequiatourism.com/history.htm. Not that writer is not named.

Niall Finneran. Slaves to Sailors: the archaeology of traditional Caribbean shore whaling c.1850–2000. A case study from Barbados and Bequia (St Vincent Grenadines). The International Journal of Nautical Archaeology (2016) 00.0: 1–18 doi: 10.1111/1095-9270.12184

Ward, N., 1995, Blows Mon, Blows. A History of Bequia Whaling. Woods Hole Mass.

Grenadines: https://www.encyclopedia.com/humanities/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/grenadines

John Edward Adams. Historical Geography of Whaling in Bequia Island, West Indies. Caribbean Studies, Vol. 11, No. 3 (Oct., 1971), pp. 55-74

Niall Finneran. Slaves to Sailors: Afro-Caribbean maritime archaeology. University of Exeter, African Archaeology Research Day 30 November 2016.

Adams, J., 1971, Historical Geography of Whaling in Bequia Island, West Indies. Caribbean Studies 11.3, 55–74

Adams, John Edward. "Historical Geography of Whaling in Bequia Island, West Indies." Caribbean Studies 11, no. 3 (1971): 55-74. Accessed August 29, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25612403.

St. Vincent Bluebook: 1868

Adams, John Edward. "Historical Geography of Whaling in Bequia Island, West Indies." <i>Caribbean Studies</i> 11, no. 3 (1971): 55-74. Accessed August 29, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25612403.

Geoff Brooks, Curator - Virgin Islands Maritime Museum https://bvipropertyyacht.com/yachting/mystery-surrounding-gloria-colita/

Brown, H. H. (1945). The Fisheries of the Windward and Leeward Islands. Devel. Welfare West Ind. Bull. 20, 1–97.

Caldwell, D. K. (1972). Odontocete cetaceans at St. Vincent in the Lesser Antilles. Year Book Am. Philosoph. Soc. 1972, 349–352.

Fielding, R. (2018). The Wake of the Whale: Hunter Societies in the Caribbean and North Atlantic. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Presently the whalers of Bequia carry out their historical, cultural activity under the IWC's regime, with the ASW quota of four whales per year since 2013...the use of traditional open boats (the whale boats used are almost replicas of the original beetle boats - the Nancy Dawson and Iron Duke - brought from New Bedford in the 1860s). Hunting equipment (harpoons, lances, bombs, guns and other tools and implements) are identical to those used over 140 years ago.

Karl Watson. The Redlegs of Barbados. Unpublished MA thesis, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL.

PRICE, EDWARD T. "THE REDLEGS OF BARBADOS." Yearbook of the Association of Pacific Coast Geographers 19 (1957): 35-39. Accessed September 6, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24042239.

Adams, John E. "FROM LANDSMEN TO SEAMEN: THE MAKING OF A WEST INDIAN FISHING COMMUNITY." Revista Geográfica, no. 88 (1978): 151-66. Accessed September 6, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40992353.

Report of the West India Royal Commission (1897:47)

Trinidad Immigration Act: https://www.oas.org/dil/Immigration_Act_Trinidad_and_Tobago.pdf

Adams, John E. "FROM LANDSMEN TO SEAMEN: THE MAKING OF A WEST INDIAN FISHING COMMUNITY." Revista Geográfica, no. 88 (1978): 151-66. Accessed September 6, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40992353.

Matthew C. Reilly. Archaeology below the Cliff: Race, Class, and Redlegs in Barbadian Sugar Society. http://www.uapress.ua.edu/product/Archaeology-below-the-Cliff,7102.aspx

St. Vincent and the Grenadines gained independence on the 10th anniversary of its associate statehood status, 27 October 1979. This module provides an overview of the key events on St. Vincent and the Grenadines' road to independence. Read about the nation’s road to independence here: http://www.caribbeanelections.com/education/independence/vc_independence.asp