Son of the Soil

–

Storytelling, mythology and ritual are at the heart of Lavar Munroe’s practice. The narrative arc of ‘Son of the Soil’ parallels Joseph Campbell’s ‘Monomyth’, where the hero embarks on an adventure, finds mentorship and hones in on skills while sinking ever deeper into the abyss, until he is sharpened in the darkness to ascend from the unknown realm of spirit with new gifts. How does one learn from the hard lessons of the loss we encounter during the hero’s return? Here, the cycle is exposed, articulated and formed.

“Perhaps home is not a place but simply an irrevocable condition.”

I. Lineage

My first encounter with Lavar Munroe’s work was in 2009-2010 doing research into contemporary practices and practitioners across the Caribbean. I came across careful renderings of works on paper full of death, magical realism, mythologies and morphologies of a people emerging out of a physical struggle, moving into another plane of existence with a different inheritance. This kind of liminality and the spirit of the in-between was the quality that struck me then, and again years later as Munroe’s work has evolved and transformed itself, literally moving off of the wall and into a spatial experience. It is quite thrilling to be a witness to years of rigour, devotion, excavating and curiosity.

Munroe's work straddles the line between painting, sculpture, and installation, challenging narratives around survival, loss and trauma in a world filled with violence; he overcomes the condition of the space to provoke new kinds of possibilities and futures. Mining mythologies—of which the hero and the trickster exist in an imaginative twain/dance—postcolonial histories and a constellation of literature collapse to bring to light a critique on stereotypes of the ghetto and social tensions therein. However, to set the scene for the work one must get a taste of the space, its colour, streets, houses, peoples and history.

“Untitled (Children and Goat on Dirt Road)”, ca 1901. William Henry Jackson. Original glass plate print on archival paper, 11” x 14”. Image courtesy the NAGB National Collection.

Born in New Providence in 1982, Lavar Munroe grew up in Grants Town, an area located in the belly of cultural Nassau, the Nation’s Navel. The historically significant, Over-the-Hill communities comprising Bain Town, Deans Town, Delancey Town and Grants Town were settled in the 1800s by liberated Africans and the enslaved who were still, in the early 19th century, working on plantations. It is not surprising at all to know that the free Africans and enslaved people that settled these areas represented the principle African tribes, the Yorubas and Congoes.

As slavery was nearing its end in the British West Indies (1834), followed by four years of apprenticeship through to 1838, regulations were put in place for free coloured people and enslaved Africans to be domiciled in quarters beyond the city limits, and thus, land settlements were developed to house these workers. This was done with the aim to keep the peace, to regulate and monitor movement, and to continue the bifurcation of races and classes, though the latter wouldn’t come into play until after the emancipation movement.

“The influx of Africans after 1807 necessitated carefully planned settlements. The first of these settlements was Grants Town which began as a government-sponsored project to provide land for the African recaptives—a freed slave; especially one seized from a captured slave ship and subsequently liberated—and which in the course of its development encompassed the extant settlements and their residents both to the south and to the north, Headquarters, Carmichael and Delancey Town respectively.” [1]

In 1825, Grants Town was formally established, and during its first ten years became a flourishing buffer community adjacent to Nassau with informal crossroad markets, meeting houses, schools and churches, and later on banks, populating the space. Being descendants of West Africans, individuals in these communities practised and implanted deeply rooted traditions and rituals that became an integral part of the lifeblood, colour and uniqueness of Over-the-Hill, setting up the culture as one drawing from African heritage.

Several significant developments arose out of this zoning, including the friendly societies and “lodges,” which were spaces to honour Afro-Bahamian culture, and with it a profound, more ritualised connection to congregation. A fraternal space of brotherly love, relief and engagement with truth, the lodges informed how men in the communities cared for each other, their families and the broader society. This kind of custodial tradition inherited from the Scottish and brought to The Bahamas circa 1837 gives us a better understanding of the context of New Providence, hegemonic structures, gender dynamics and the emergence of social traditions.

Between environmental devastation brought by hurricanes—two major ones in 1846 and 1866—a fatal tornado in 1850, and several cholera and yellow fever epidemics, the resilient communities of Grants and Bain Town found their footing, and the landscape transformed from desolate swamp terrain into a thriving group of mobilising and enterprising communities, contributing to an urban sprawl during the close of the nineteenth century. Through the boom of the late 1890s, coupled with continued blossoming of the tourism industry and the hurtling towards Majority Rule, this social mobility ignited a fire and a thrust towards Independence. This momentum changed the course of The Bahamas, ushering, the archipelagic colony into self-governance in 1964.

The emergence of this new country, one filled with hope and the knowledge of the quiet, subversive and somewhat brutal but lingering revolutions—Burma Road Riots (1942), Black Tuesday (1965)—were felt acutely in the heart of New Providence. Over-the-Hill rose to become the epicentre of activism and the leading site of resistance and freedom fighting, and in Mason’s Addition, a .20 mile stretch of street and Sir Lynden Pindling’s birthplace, all of this history, ritual and struggle to resist, exist, thrive and collide took place, leading to independence in 1973.

Grant’s Town (Nassau, Bahamas), circa 1915. Photograph Albums Collection, History Miami Museum, 1990-515-150.

II. It Takes a Village

Fast forward several decades later, and we are in a different Over-the-Hill. No longer thriving and bustling with industry, entertainment—renowned jazz clubs which impacted the lives of many visual artists, including Max Taylor and Kendal Hanna—and well-kept historical landmarks, these communities have now fallen into neglect and disrepair. Poverty, violence and gang warfare have taken hold and shaken them empty of their richness, and inhabitants are left to contend with the undervaluing of their lived-in spaces, environments and lives.

“Many cities across Latin America and the Caribbean share a common issue: the abandonment and underutilisation of central areas or downtowns. In most cases, city centres are bustling with activity during the day, but become ghost towns during the night. This is the case of Nassau, a city where its downtown area, rich with historical landmarks and local treasures, becomes almost completely silent and vacant after sunset.” [2]

Even so, you cannot entirely stifle culture, the creative spirit and the power of history; its routes and roots. In the midst of oppression, trauma, and in the worst of times, this spirit rises to rescue and resuscitate. This site is where the ingredients come together to locate, inform and position Munroe’s curiosity and excavation.

To give a snapshot of the artist’s early life: he enters his first Junkanoo shack—the work and studio space for Junkanoo groups to congregate and create costumes for the annual and seasonal competitions—at the tender age of six or seven to act as company for his uncle, Gregory “Skinner” Curtis, a lead designer in the Saxons Superstars group. Recruiting many of their numbers from Mason’s Addition and the surrounding grass root areas, the Saxons—an established lead group—exemplifies an identity of pride and belonging. It is worth noting that visual artists Jackson Burnside III, Stan Burnside and John Beadle were once a central part of this group, indeed leaving an impression on Munroe’s early start.

Moving from his family home on Milton Street when his mother died in 1992, in order to live with his grandmother, educator and teacher, Sadie Curtis, on Laird Street, three blocks north of Milton, was a significant change for Munroe. To say how his mother’s loss impacted his sensibilities at such an impressionable age is left up to the imagination and experience. Munroe lived with his grandmother full time for two years before moving back home to live with his father who raised him as a single parent.

However, having his uncle’s shack in the backyard of his grandmother’s home surely made the transition and loss easier to bear. This was just one of many shacks—it is hard to estimate the number of shacks that were in existence decades ago—but today, three prominent groups occupy the Over-the-Hill/Centerville locations, namely One Family, Roots and the Saxons with an estimated seven, six and thirteen shacks respectively.

Junkanoo is a long-standing cultural tradition that is now ultimately a national symbol of Bahamianness. It has been practised for over 200 years across the archipelago, and is a West African syncretic festival that embodies the spirit of this island’s people through procession and performance. Representing poverty and wealth, discipline and rebellion, competition and cooperation, creative genius and physical prowess, it [Junkanoo] is simultaneously viewed as the quintessential Bahamian self-conception, and the best face turned to the visitor. Like street festivals everywhere, it can be classified as a ritual of rebellion, a politico-cultural movement, or an annual invocation of the liminal.

Showing border (Grant’s Town, 1937). Pro 5-10-21. Image courtesy of the Department of Archives. Nassau, The Bahamas.

With roots in the mythological African past, it is not surprising that another world of fantasy, escapism and a domain of adventure captured Munroe’s delight and interest. Not being allowed to participate in actually building the costumes, as a child Munroe was nevertheless able to witness and experience first hand the assembly line, skill sets, and camaraderie of the shack. This was a critical informal education, as he was introduced to colour, shape, form and movement, along with building and collaboration. This was a hallmark and foundation, as this sensitisation implanted the seed which would later spawn greater interest as Junkanoo began to inform and transform his world purview.

As a teenager, he was able to move closer to the production and get a better understanding of composition and where the magic and difference happens: on paper with the drawing and, more importantly, in the research. Research is a significant component of Junkanoo as each year themes are selected, and groups invest a significant amount of time brainstorming the history of the traditional theme in order to build out context and interpretation.

It was in this space that the world opened up for Munroe as images of Ancient Egypt, Greece and China and a host of different histories fell out of the many pages that he stole time to review. Replete with religious imagery, since it is reasonably common for the annual procession and competition to draw from themes that are popular and connected to the development of The Bahamas as a predominantly conservative Christian country, devils, angels, demons and the like started to emerge.

In 1982, the year of Munroe’s birth, “Skinner” was drawing the lead design work of a Devil for the Saxons. They did not win on Boxing Day that year, but took home the New Year's Day prize under the theme ‘Protect our Wildlife’. It is a bit serendipitous to know that Munroe came into the world with iconic imagery of devils being present. Today, this imagery still rings seminal as an established memory weighted in the inquisitiveness of childhood, connected to the sacred and the profane—elements that, to this day, linger.

‘I Survived Devils of Cat Island’. Junkanoo Costume of Devil designed by Greg “Skinner” Curtis in 1982. Image courtesy of Grey Curtis.

Books became a central part of Munroe’s adolescent world as a space to develop and hone in “cultural intimacy,” as Junkanoo inherently addresses diasporic issues of attachment and belonging connected to postcolonial identities linked to displacement and uprootedness/groundedness. These dichotomies come to the surface of his work, and as he transitioned from The Bahamas to the US to formalise his education at Savannah College of Art and Design and Washington University. He employed this interest of research as a means to defend and build the histories, mythologies and patterns utilised in his work.

So this is the space from which the son of our soil breathes; this is how he fills his environ with markers of memory, signs and rituals from a place that some of us are familiar with, and a place still foreign to others. This is how he makes sense of a cultural excretion, using foundational tools to strengthen his arsenal and weaponry, to dig into the history and unearth the heroes, the trickster, and the monuments of the African diaspora.

Today, Munroe still has a studio which is an active site of production at his family home on Milton Street in Grants Town, a domain from where he articulates, consolidates, and imagines different futures for the people around him and certainly for himself.

III. Constellations

Drawing inspiration from everyday occurrences within society—literature, fables, folklore and mythologies of every kind—Munroe uses all of this as fodder to build a personal universe; populating this expanse with a kind of morality that one cannot, in this globalised world, dismiss.

Curator Okwui Enwezor shares that, “contemporary art today is refracted, not just from the specific site of culture and history but also—and in a more critical sense—from the standpoint of a complex geopolitical configuration that defines all systems of production and relations of exchange as a consequence of globalisation after imperialism.”[3] This is at the root of questioning that informs postcolonial practices—Munroe's included—and the conditions of working within spaces that allow for the movement, recalibration and certain shifts accommodating the amalgamation of cultures.

Édouard Glissant went on to further clarify that mythology is important as it disguises while conferring meaning, obscures and brings to light, mystifies as well as clarifies, and intensifies that which emerges, fixed in time and space, between men and their world. It explores the known-unknown.

It is in the threshold of this known/unknown space that Munroe fixes his gaze and heart, looking closer at more sinister, dark and brooding realities/underbellies/betrayals of modern day economies, capitalism, excess and sovereignty. The last decade of Munroe’s practice covers the spectrum and the arc of development that details and exhibits the nuance of how the work evolved in density, darkness, compassion and breadth.

Starting with the ‘Specimens’ series from 2008–2010, we are looking at a different kind of history, one that is perhaps more complete, just and fair. Oftentimes in postcolonial spaces, and certainly the Caribbean, there are fables of erasure developed around the indigenous and legends of the “discovery” of the New World. With this index, he combines science, genotypes, astrology, archetypes and magical realism to draw a map to illustrate a kind of cultural loss significant to the New World. There is a specific capacity in the work to blend the supernatural and allegory, so that hybrid animals and human beings illustrate and return compassion and empathy to our space.

Llamulga of the Fertile Land, 2011. Graphite, spray paint, sea salt, acrylic and marker. 12” x 8”. Work courtesy of Lawrence Bascom.

Created on paper, these pieces employ drawing, collage and painting with erasures that are significant on surfaces embellished with gold leaf in slight, very poetic ways. This material is used to fill moons, horns, ruffles on a collar, and sometimes the rough gesture of a woman turning into a mermaid turning into a hook. The figures are haunting, lost and trapped between their plane of being and our projections of what we learn about the Lucayan, Arawak and Taíno populations. The myth of complete loss is also brought into question as we struggle to reckon with the strong and demure qualities of the figures. Researchers recently found evidence in Preacher’s Cave, Eleuthera, that the Taíno, the first indigenous peoples to feel the full impact of European colonisation after Columbus arrived in the New World, still have living descendants in the Caribbean today.

The ‘Specimens’ are dense and potent, and are an acknowledgement to the malnourishment that is often wrapped up in our history and education. Alchemy shows up to dull the fact that we are looking into a fantastical world because so much of our space, its environment, ecology, nature and folktales were stripped of their material essence, by force, (dis)ease and by action.

Specimen: k3-1586, Sus Amalingopae. 2011. Graphite, spray paint, glass beads, latex house paint, sea salt, wire and glitter. 10” x 8”. Work courtesy of Lawrence Bascom.

Munroe’s weapon of remembering and allowing space for this multiplicity is his skill of assembling these subjects and interests, and through the amalgam we witness a revival and the breathing of a new life into a malnourished and depleted history. The ‘Specimens’ hang in shadow boxes, ready to be studied and examined, and as you get close you see a bit of the trickery that will emerge prominently in his practice in the years to come. The emergence of the trickster as an archetype defies duality, embodying both light and dark, heroic and villainous, foolish and wise, benign and malicious qualities. This universal paradigm with evasive behaviours and tendencies can be linked back to cultural traditions from West Africa and the sharing of the infamous Anansi, the spider and ultimate trickster, originating with the Akan peoples of West Africa. This is used as a way to transgress patterns, and as another way to intersect contemporary notions of history.

An attack on cultural amnesia is embedded in all of this work as beauty, fragility and strength dance in these disembodied/embodied figures. If the trickster is the breaker of taboos, then he finds a way to almost cannibalise the culture that he has come from, digesting its material and assimilating its content in a way that allows for the destruction of the dangerous monolithic narrative of Caribbean artists only working in one way: with the beauty, lushness, colour and peace of the landscape, further perpetuating the myth of Paradise.

It is with this political motivation that Munroe thrives. With the archetype, he can unleash a host of different ways to enter and perform in his work. Through the shacks, these traditions, oral and otherwise, were so compelling and subliminal that this experience affected and stayed alive despite crossing the Black Atlantic hundreds of years ago.

In the series ‘Grants Town Trickster’ (2012), Munroe’s interest to work with cardboard and scrap material is something that has remained in his consciousness since he was a child. Being one of the main materials used in the creation of Junkanoo costumes, cardboard was able to present a challenge and evolution in his practice, moving his focus from traditional paintings on canvas and collages to sculptural pieces that emanate the darker conditions of impoverishment in The Bahamas and certainly in the United States, where Munroe has lived and made work for over a decade.

“Munroe’s weapon of remembering and allowing space for this multiplicity is his skill of assembling these subjects and interests, and through the amalgam we witness a revival and the breathing of a new life into a malnourished and depleted history.”

Cardboard is typically used as a material of commodity. Its commercial production began in 1817 in England, and it populates our modern day world as a means of processing and packaging the export of goods from first world manufacturing countries. Regardless of class, it is a material that we all encounter. It is ubiquitous. In The Bahamas it is certainly plentiful and used in abundance for the Junkanoo festival. By choosing to consciously work with a material that is so delicate, yet cheap and connected to oppression marked by the perpetuation of poverty and excess waste that changes the face of the ghetto communities of the United States and the people therein, it acts as a marker of how Munroe chooses to politicise, critique and question the symbolism/intentions in the material itself.

‘The Law’, (2012). Signed en verso. Acrylic, spray paint and tape on cut canvas. 60” x 108”. Work courtesy of Private Collection, United Kingdom.

Munroe shares, “There are similarities between The Bahamas and the United States in regard to societal structures and economic deprivation among poorer class blacks who reside in the ghetto. Like the ghetto in America, the ghetto in The Bahamas is an unstable place where many people are undereducated, mis-educated, uneducated, and left unfit to compete in the larger job market. As a result, many turn to lives of crime. I retain my sense of pride to be from the ghetto, and have learned to use the negative stereotypes of the ghetto as fuel for my visual investigations.”

Munroe—trickster-turned-scavenger—continues to use Grants Town as a site, both physical and imagined, as a locale of study and inquisition, ingesting the conditions of the stigmatised and marginalised along with the effect that this has had on his mental, physical and emotional development and being. This biographical work shows the journey and the plight of being able to navigate through nebulous, and at times, violent and unsafe spaces while using the tools of vulnerability to create a different kind of momentum and upward mobility.

There are several pieces from the series including ‘Bushmen: Tale of Twin Gods’, that recall another seminal moment from his childhood. Using the image of the goat’s head—a powerful image in the constellation and memorial to childhood—the figure in this work blossoms and becomes a giant, menacing and broken with uneven sticks for crutches, beaded necklaces, Winnie-the-Pooh toys for eyeballs, and fake flowers. Found objects populate its embodiment. With the mouth stitched up with cardboard, there is an inferred violence in the action of the sewing and the muting of a voice. This hybrid, broken but beautifully embellished creature becomes an icon dragging its weight and abuse in clear sight.

‘Bushmen: Tale of Twin Gods’, (2012). Mixed media. 108” x 46” x 62”. Work courtesy Walter De Weerdt at Nomad Gallery.

This abuse, neglect, corruption and the misuse of power is evident in ‘The Law’ and speaks to this current scourge of our time. The rise of the impoverished, the sprawl of inner city communities and the ghetto is a commonality in developing countries, and it is not hard to see that Munroe pulls from his environment in very particular ways—engaging with graffiti, tears and intimidating figures that threaten. All of this is a call to shake up the establishment and status quo, another device to question the value of Black lives everywhere. This underlying questioning and interrogation is a silent but explicit quality of the work.

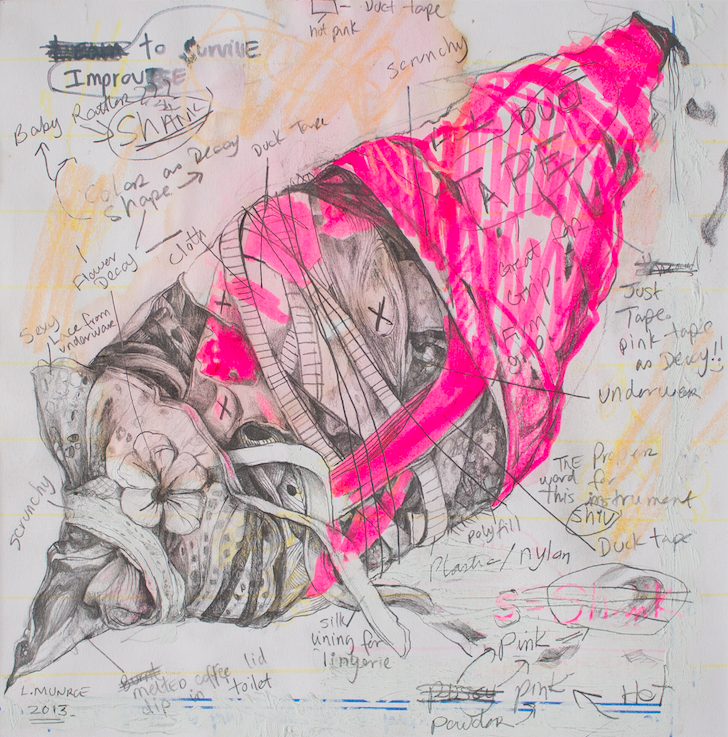

Munroe's creative practice and its materials continued to proliferate and develop off the wall and into a richer dimensionality, at once exploring the fragility and tenuous relations of the human condition, Blackness, the grotesque and the beautiful. His ‘Shank=Survival’ series from 2013 pulled no punches, and went straight to the heart of how Black lives continue to be threatened by institutionalised racism and its relationship to the prison system, which is toxic in terms of human rights and justice. In the United States, the racial and ethnic makeup of prisons continues to look substantially different from the demographics of the country as a whole. In 2016, blacks represented 12% of the US adult population, but 33% of the sentenced prison population. Whites accounted for 64% of adults but 30% of prisoners. And while Hispanics represented 16% of the adult population, they accounted for 23% of inmates.

In many poverty-stricken communities, serving time in prison is considered a rite of passage. It is where you go to toughen up, to excel in leadership, to develop a new kind of social ammunition and to enhance your relationship to masculinity—toxic or otherwise. Prisons are breeding grounds for the worst and the best in humanity. In the ‘Shank=Survival’ series it is important to note that the objects themselves, while stunning, are informed by drawings on paper that are equally exquisite in their rendering. There is an implicit disguise and a shrunken abstraction of the blade within the construction.

Lessons on Foraging Magical Weapons known as Shanks (no.5), (2014). Marker, white out and pencil on paper. 9 1/2” x 9 1/2”. Work courtesy of Lawrence Bascom

Random found objects appear in handwriting jumbled across the sketches: lace from underwear, decayed flower, baby rattle, scrunchy, lid of toilet, duct tape, silk lining for lingerie, pink powder, nylon and underwear that constitutes a shank—a weapon commonly used in prisons to defend oneself. These things taken separately are innocuous. In fact, most of the found objects are in many ways gendered and feminised. The use of hot pink throughout the series is notable. As a way to make the object at once beautiful and almost invisible, various things are done to bring it into the physical world. Skilled in every sense as Black men navigate the social system of prison, relationships are formed, battles are lost and won, and these devices for protection and for wounding lay bare the conditions of a kind of terror that impacts the humanity and the spirit of each individual trapped within this cycle of despair.

‘Shank #2’, (2013). Metal, cotton, cardboard, duct tape, rope, thread, rubber, fabric, pearls and fake flowers. 22” x 6 1/2”. Work courtesy of Lawrence Bascom.

But what is seen as despair, trauma, torture, embarrassment, isolation, shame and death from the outside, is different on the inside. Munroe is pointing to these former realities, but also exploring the environment of prison as one where there is the potential for intimacy, brotherhood, and an understanding of the male-self in relation to others.

The shanks is a weapon with which its carrier defends the unknown. It is within this space that we can see the beauty of the object and the rendering of it. We can also easily see a hero rise to defend, we can see the humane qualities come to the surface and bubble over the chains of entrapment.

‘Fallen’, 2016. 60” x 60”. Acrylic, latex, house paint, spray paint, staples and string on cut unprimed canvas. Work courtesy of Jenkins Johnson Gallery SF/NY and the artist. ‘Fallen’ appeared in Season 3 of the Fox hit series, “Empire”.

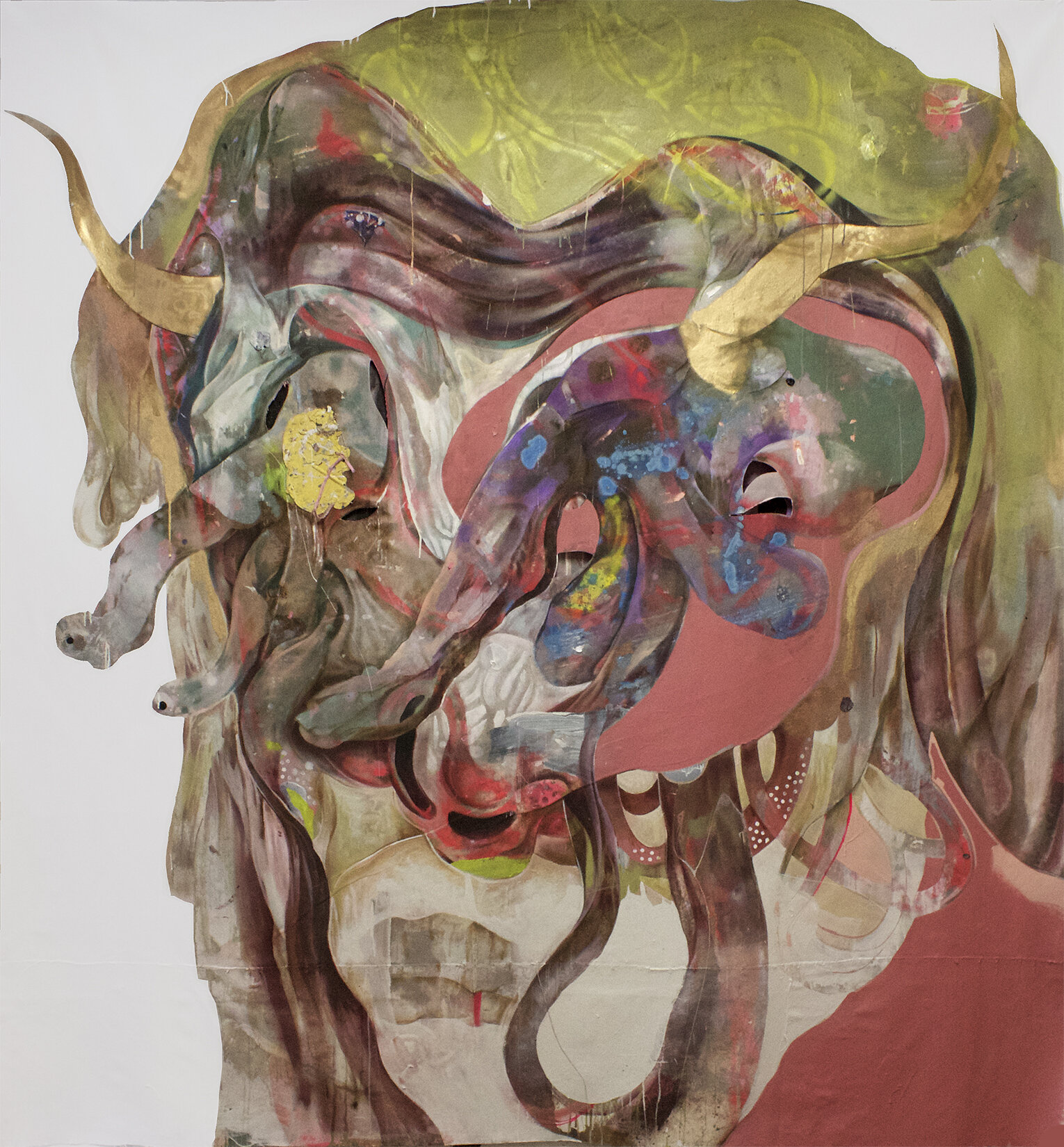

In 2016, a new series consisting of 12 paintings entitled ‘Devils’ emerged. The oversized and somewhat bulbous hybrid shapes consume the plane of each canvas, with various protrusions and crude markings with hints of the macabre spilling out or being sucked into the representation itself. Somewhat abstract, visually the stories told are altogether one of mayhem, stark violence and trauma. Munroe, again working with the environment he immersed himself in the US, started to troll and walk the streets to conduct a type of survey. The neighbourhoods that he found were reminiscent of Grants Town, with gang symbols and logos populating the space, the visible hint of how this violence continues to shape and mark his life’s interest and work.

The devils are mappings of survival for the artist. In the images there are hints of darkness, fear and anger, the left over residue of how race relations have significantly altered the plight of Black people, in particular the black male. ‘And Night Dwelling Villagers…(Devil no. 4)’, is particularly jarring, with a single eye staring at you. The physical appearance of these devils are wretched; with broad noses and ample mouths that slip and spill over the canvas, and the only element of hope is several cuts in the canvas where one is allowed to project a possible future. Even if it is hard to see hope, it is there, locked in the didactic approach taken to integrate art historical representations and literature. These offer a murmur of beauty, and Munroe acknowledges the significance of the duality of consciousness as the devils act as both portraits and disguises. Disguises for whom? Perhaps police, politicians, clergymen and terrorists, the major arbiters of corruption, injustice and inequality in today’s world.

IV. Sojourn

What perhaps encapsulates the intertwining of an intense care and love after losing his father in 2015 to stomach cancer, Munroe created a series of homages and memorials to acknowledge the bonds in this life and the afterlife that fused them into a posthumous collaboration with his deceased mother, Beverley, who died in 1991. Memorials comprising a ceramic funerary urn, which housed his father’s ashes, and a soiled parachute—with stains, patched holes, oils, sweat, sea salt, sand and ropes—sewed and braided by his father prior to him being hospitalised, are extensions by which Munroe’s father is able to travel with the artist. This activates and completes their promise of journeying and collaborating in order to have their practices, passions and lives overlap—to embrace your inheritance, to collect and to remember for permanence sake. While sombre, it is a powerful marker connecting back to ritual, and in particular one of the primary sources of literary inspiration for Munroe. Using Joseph Campbell’s ‘Monomyth: The Hero with a Thousand Faces’ (1949) as an anchor and a structural device, this memorial signals stage nine, the return of the hero. Coupled with a continuing project ‘And the Dogs went Silence’, which moves more succinctly into the journey to the returned or the resurrection, these actions connect to the idea of legacy, forgetting, and building one’s personal mythology.

Installation from “Son of the Soil” at The National Art Gallery of The Bahamas in 2018. Image courtesy of Jackson Petit and The National Art Gallery of The Bahamas.

“The hero again crosses the threshold of adventure and returns to the everyday world of daylight. The return usually takes the form of an awakening, rebirth, resurrection, or a simple emergence from a cave or forest. Sometimes the hero is pulled out of the adventure world by a force from the daylight world.”[4]

“As a metaphysical challenge, viewers are left to contemplate the surrogate oversized humanoid figure suspended from this soiled parachute in a foetal position, ready to be reborn again or enter a new culture, a new space with difference all around.”

As an active gesture, bounding ashes from his father in an urn and showcasing this in various parts of the world, his father has the chance to sojourn with the energies and moments in the work. As a metaphysical challenge, viewers are left to contemplate the surrogate oversized humanoid figure suspended from this soiled parachute in a foetal position, ready to be reborn again or enter a new culture, a new space with difference all around. They are also left to ponder the remains of a powerful figure, as the earthly passage and loss is something that touches all parts of our humanity.

The iterations evolve and take on new compartments, however they never lose the spirit of honouring the place of origin. Grants Town, a place of community, a space forged by the will of the African diasporas and the spirits that toiled hard to ensure that these kinds of histories, mythologies and narratives will not be forgotten. Within the change and loss there is erasure, but erasure will not happen consciously. In fact, Munroe’s work leaves us with a marked repopulation and retelling of a space that is ripe with life, and defined by resistance.

The power to rewrite, diversify and give other meanings to our surroundings is what was done over 150 years ago in the Over–the–Hill communities, and as the Munroes return to Nassau, we celebrate the return home of two Heroes: a son and his light.

-

[1] Bowe, Ruth M. L. Grants Town and the Historical Development of ‘Over-the-Hill’. International Journal of Bahamian Studies, Vol. 3. 1982. https://journals.sfu.ca/cob/index.php/files/article/view/73/42

[2] Chona, Gilbeto. Nassau Urban Lab - Central Nassau Urban Regeneration Plan. 2017. https://issuu.com/rolandkrebs7/docs/nassau_screen

[3] Enwezor, Okwui. The Postcolonial Constellation: Contemporary Art in a State of Permanent Transition. 2008.

[4] Campbell, Joseph. Monomyth: The Hero with a Thousand Faces. 1949.

All images in slide show courtesy of Lavar Munroe, The National Art Gallery of The Bahamas and Jackson Petit.